American Ownership

My husband and I bought our first home when we were 24. Hard work had nothing to do with it.

This is the second installment of a three-part series about home ownership in America. This essay stands on its own but is definitely best understood after a read of the first installment. You can find the first piece here.

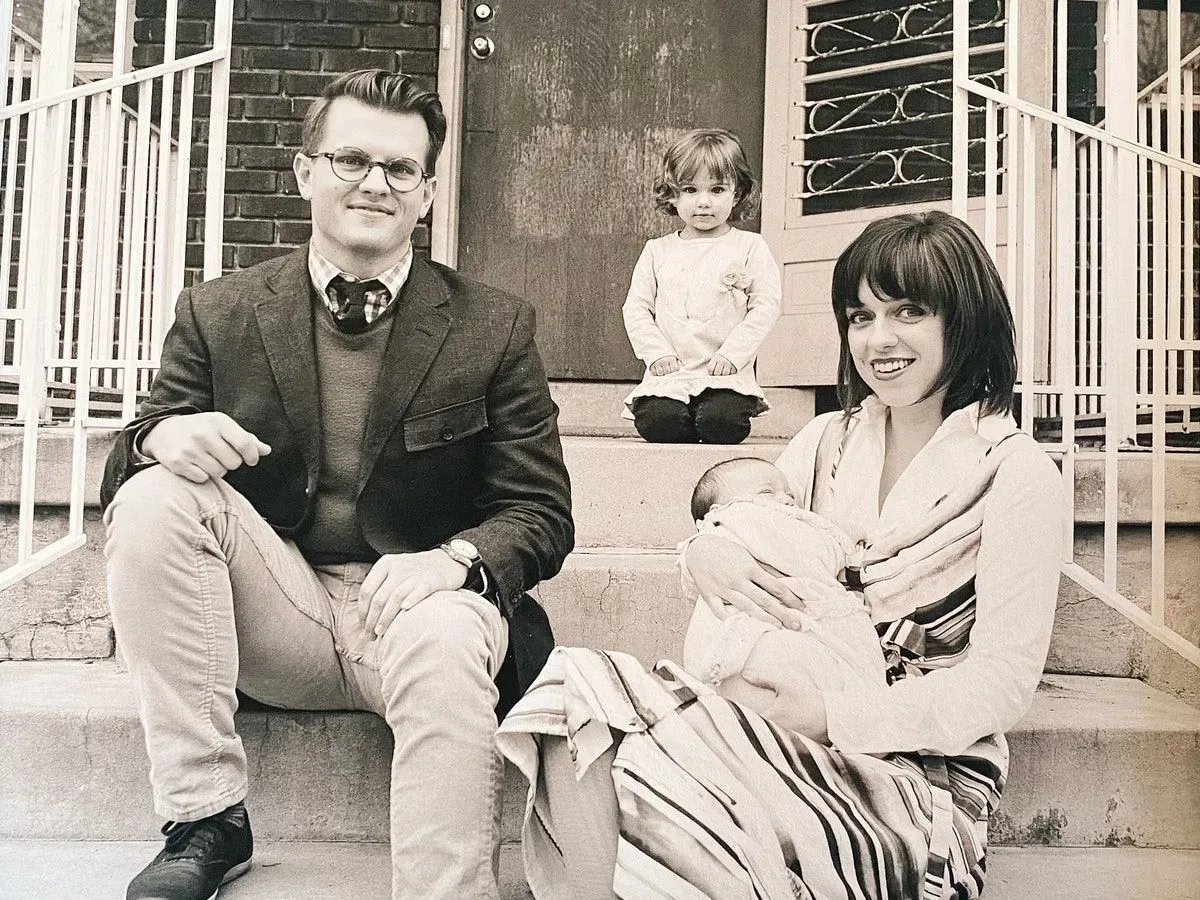

My husband and I bought our first home when we were twenty-four.

It’s important to be honest here. This wasn’t some triumph of good sense and hard work. It wasn’t accomplished by making our avocado toast at home instead of ordering it in a coffee shop. We didn’t work five jobs each to do it. When we got married at 21, we had good credit. Neither of us had ever had to charge rent to a credit card and then fallen behind on payments. We’d never been uninsured and then had a medical emergency that left us swamped with medical bills.

While neither of our families gave us money to “get started”, we didn’t really need it. There was a program for first-time homebuyers with good credit that required just a 3% down. For us, that meant a down of $6,000. Not a small sum, but one we were able to cobble together. This cobbling was also not the result of superior character or restraint. We were able to save the money because we didn’t have student loans. My parents paid for college until I dropped out to have a baby. (Another story, for another time.) Riley paid for college through a combination of scholarships and a great-aunt’s education trust that paid out up to $2000 a semester.

Buying that house at twenty-four and selling it years later, started a sequence of modest, but impactful, wealth building. We’ve rented on and off between ownership. But that first house purchase helped us make and keep the down payment for the subsequent houses we bought. Our lives changed because of our first home purchase. Our children’s lives changed too. Our middle child was diagnosed with binocular vision problems and dyslexia, both issues our insurance wouldn’t pay to treat. We were able to take a little money out of our current home equity to pay her therapy bills.

Do you see the cycle here? We had access to that first home loan because of the privileges of our childhoods. Privileges like consistent health insurance and education trusts. Because we got that first home loan, our children have access to privileges in their childhoods. Privileges like vision therapy and teachers trained to work with dyslexic minds.

Home ownership provides access to privilege because, when the terms are fair, it is the number way one to build wealth in this country. This means renters and their children are left behind economically and socially. Why do we need wealth to get ahead in America? Without a comprehensive social safety net, American citizens need consistent individual financial security. It could be argued that health insurance, education, therapy that makes your eyes work should all be rights! But in America, they are not. And in America, profitable home ownership is both predicated on access to those things and gives access to those things.

This is a policy problem. We need to change how wealth is built in America. One way to do this is passing policies like Universal Basic Income, rental subsidies as impactful and wide reaching as mortgage interest tax deduction, and higher taxes for the 1%. Will this result in less personal wealth? In some categories, yes! But mostly, the wealthy will still be wealthy - just one yacht wealthy instead of two yachts wealthy. They’ll survive.

While they survive? A renting single mother of three will have enough money to weather financial storms like loss of income and health emergencies. (You know what? Let's throw accessible healthcare in the policy pot! Let’s stop bankrupting mothers over their children’s cancer diagnoses, huh?) We need comprehensive renter protections. And on top of that, which isn’t much for a country with our means, we need to build more housing. More housing to buy and more housing to rent. We need more housing available for subsidized purchasing and subsidized renting.

Homeowners are typically opposed to more housing in their communities. Why? More housing can drive down property values in markets driven by scarcity. More housing means more renters. Many homeowners dislike renters because they are perceived as being less invested in the community. This is, of course, nonsense. More housing means more people and more people often means less homogeneity. More housing can mean affordable housing. Lots are developed with an affordable multi-family housing unit instead of a single million dollar residence. Each of those units give many families access to neighborhoods. They also mean one less affluent household contributing school inequality with PTA Champagne and Caviar fundraisers. More housing means propping open the guarded gates to your community. Sometimes literally.

Ahem.

When homeowners fight more housing in their communities they don’t use any of the above arguments, of course. They talk about the “character” of their neighborhood, even though the character is mostly just single-family zoning. (You can keep real character AND let an eight-plex in down the street! I promise!) They cite pollution concerns, even though multi-family housing is one way to fight climate change. They want to make sure everyone has access to a home, they really do, but maybe it’s best if that access happens somewhere else. And the homeowners win. Because they are what William Fischell called, “homevoters”. Homevoters are a large established group of people with a financial stake in the community who vote exclusively to protect that stake. They’re not so different fromeight year old me. They’ve got their single Disney stock clutched tightly in their hands. They’re not about to let an apartment complex lessen the value of their holding, or ruin their view.

This isn’t just a policy problem, it’s also a cultural problem. Why do you think Americans build 5,000 square foot homes? They do it because houses aren’t just homes, they are financial tools. Financial tools that also act as physical proof you’ve attained the American dream. The bigger the home, the greater the evidence of your own financial success and stake in the community. In turn, we devalue the homeness of rented homes because racist and classist policies teach us that exclusionary home owning is how we build community. We must untether worthiness to participate fully in the American experiment from a mortgage statement with your name on it. We must make simply being in an American community enough of a stake to grant you a voice. Once home ownership is no longer proof that you’re living the American Dream, suburban houses with basketball courts built into the basement will no longer act as symbols of hard work’s just reward.

If we devalue enormous houses, we’ll begin to value community centers. You see, if our homes don’t have invite-only basketball courts, we’ll not only agree to pay the taxes that build community centers, we’ll actually use them. As we invest in and utilize community spaces, we’ll actually get to know our American community. And in knowing our community, I believe we’ll feel driven to help them feel at home. We’ll build more homes, sure. We’ll change our attitudes about people who rent. And we’ll vote to implement robust affordable housing plans in our own neighborhoods. We will ensure that the most vulnerable among us are not left unhoused by the whims of circumstance.

Home ownership in America is a rigged game right now. But I don’t think we should give up on home ownership as a concept. There is a reason even the most aware of us buy into the current crooked version of home ownership. Many people find something of value in owning the place they call home. There is something compelling and comforting about sanding old wood floors until they are new again. About planting a tree and knowing you’ll be able to watch it grow, its limbs spreading out and roots growing down. There is, for many of us, something humanizing about the right to tear down walls, to build them up again and paint them whatever color we damn well please. Owning a house in order to have a stake in America is an engineered concept we should reject. But there is something about owning your own home that helps many people feel they have a stake in their own lives.

While not a universal desire, I do think it is a worthy one.

Let everyone who wants a home of their own, reach out and have it. Not because their reach was far enough, but because we reached back and handed it to them.

So what do we do with all of this? How do we reject the current framing of owning a home in America, while extending access to home ownership to more people? How do we value the rented home and the people within it? How do we make all kinds of homes - single family, multi-family, condos, co-ops, available in all kinds of ways? At market price, for rent, subsidized by generous government programs to all kinds of people? If owning a home shouldn’t be part of the American Dream, what should replace it? And what concrete steps can we take to make all of this happen? Read the final newsletter in the series.