Fire and Food Kisses

Before the stove debate simmered, fire formed us.

Writing is labor. In order to write this, I read 28 academic articles. 14 of them made it into the final draft. I learned about chemical reactions, human digestion, Paleolithic energy sources, the history of cooking and cave ventilation. The learning, the digesting and the drafting took every hour between 8:30am and 5pm for weeks. I guess I wish this kind of work required less time. But it doesn’t. If you appreciate my work, please consider financially supporting it.

First, I’d like to introduce, Cooking with Gas: a newsletter series about the stove

When I logged onto Twitter last month, my feed was full of people trying to figure out what to do about gas stoves. Fossil fuels are polluting our present and burning up our future. And cooking with gas creates high levels of indoor air pollution. It’s not unreasonable to try to figure out what to do with that information. There was a lot of nuanced discussion. I appreciated it.

But there was also the extreme discourse that Twitter promotes. I saw one account claim that having a gas stove in a house with children was child abuse. Other accounts seemed certain that the government was about to stalk into their homes and take their gas stove, along with all their rights. “Give me methane or give me death” patriots, I guess.

We’ve long known that fossil fuels cause climate change and that gas stoves are a source of indoor pollution. So why was the debate heating up?

The Institute for Policy Integrity issued a report about gas stoves last April. According to the report, homes with gas stoves have daily nitrogen dioxide concentrations “almost five times higher than WHO’s 24 hour guideline.” The concentration of particulate matter in homes with gas stoves also exceeds WHO’s guideline. This is especially true in homes without proper ventilation.1

The report called for ventilation requirements, safety standards for gas stoves and an investment in public education about the dangers of gas stove emissions. It never called for a complete ban on gas stoves. Last week, a representative from the Consumer Product Safety Commission referenced this report in an interview. Referring to future stove manufacturing he said, “Products that can’t be made safe can be banned.” Which is, obviously, different than calling for a forced recall of the stove you used to cook your dinner last night.

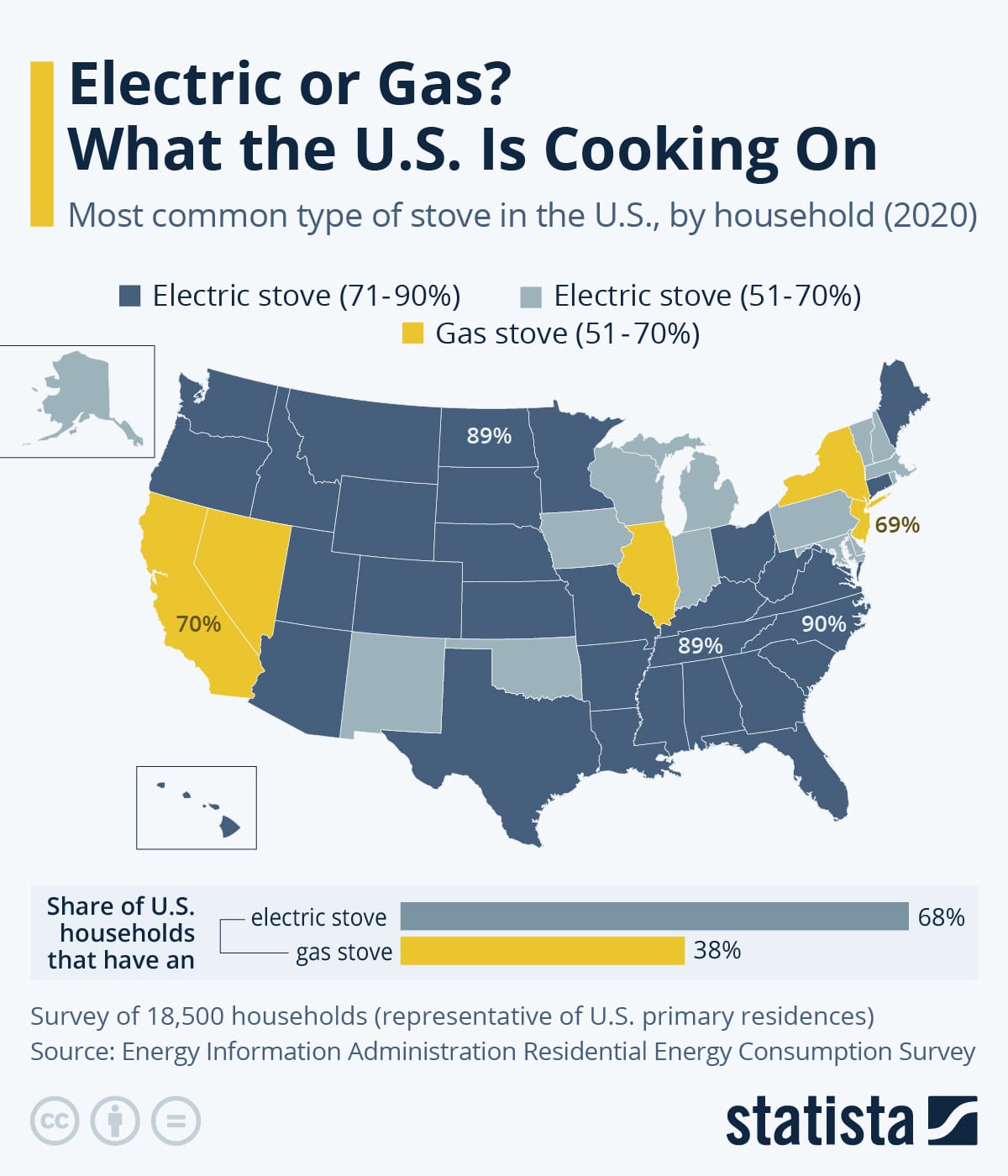

Although when I say you, I am talking to a minority of people potentially reading this newsletter. Only 38% of American households have a gas stove. According to the Energy Information Administration, 68% of American households have electric stoves. In most states, over 70% of households have an electric stove. In places like California, that number is closer to 90%.

The American home is overwhelmingly already converted to, and wired for, electric cooking. And many homes that are not, will be soon. The Inflation Reduction Act includes significant rebates for purchasing and installing electric appliances. Improved heating technology, like induction, combined with financial incentives will lead to a further adoption of electric stoves. But on both sides of the Twitter stove debate, I saw people acting as if the American household was defined by the gas stove. It’s not. But many ideas about the American home absolutely are.

In America, the stove has always been a device used for more than cooking.

Some used a fictional Gas Stove America to paint Americans as clinging to fossil fuels and charred peppers. It was offered disdainfully, or hopelessly, as further proof of a shared American hatred of the environment and children. Others used a pretend Super Majority Gas Stove America to proclaim that the sweet flame of liberty still burns in the heart of each American home. Standing astride their Twitter account, they promised no one was going to extinguish that fire, not on their watch.

It’s infuriating, but not at all surprising. In America, the stove has always been a device used for more than cooking.

Over the course of this newsletter series, I am going to write about commodification of the stove and the energy that heats it. So far, I’ve got five installments outlined. A few things* we’ll cover:

Formed by the fires of the Second Industrial Revolution, the stove sits in the fractured center of the separate spheres.

White supremacy, the iron stove and controlling the means of sustenance.

How the stove was used to pioneer domestic data collection and helped to commodify the American home. There’s no Amazon Smart Home without the 19th century stove industry.

The war between consumer capitalism and Soviet-era communism, with the stove kept at the front lines.

How the stove has become a flashpoint in the fight over what kind of energy can keep a house a home, and the earth inhabitable, even as our energy grids crumble.

But first, I am going to write about a world before factories, data-mining, marketing and even the discovery of iron. Because before we can talk about 200 years of simmering stove debates, we have to understand how the stove’s mother, the hearth, transformed and preserved us.

*including, but never limited to - you know me, ha!

Fire and Food Kisses

My youngest daughter used to think the way we are now is the way we’d always be and have always been. Like we came to be just after the stars. She thought our family was an element, not a compound.

Sometimes I’d show her a picture of me as a kid and she’d laugh, “Mama, you were never a kid!” Babies became kids but grown ups were always grown ups. She didn’t laugh when she’d see pictures of our family before she joined us. She’d search the picture, looking for her face, “Where am I?” When I’d tell her she wasn’t born yet, she’d cry, “No, I am there. I am right there.” And then she’d point to her oldest sister, who she really does look like.

Her sisters were nine and six years old when she was born. She’s always understood they were bigger than her. But for a long time, she thought they’d all eventually be the same age. And then they’d play together, only coming inside when Riley called them for dinner. We’d sit around the table together until …I don’t know when. Little kids think forever and a minute are the same thing. So maybe forever, maybe a minute. I am not sure what preservation method she thought would keep us. But whatever it was, she had great faith in it.

Over the past year, she’s begun to understand that the five of us won’t just continue on as she’s always known us. We’re not elemental. And even our love for each other is not a strong enough preservative. We won’t keep. We’ll continue to be transformed, as a family and as individuals.

Her sisters will always be older than her. They’ll never get to be five or ten or fifteen together. And they won’t get to stay together either, not the way she’d like. Kids do turn into grown ups. They move out, visiting home when they can. None of it makes any sense to her. How can home become a place you visit? (It’s a good question honestly. And one I’ve never been able to answer in a way that satisfies the ache in my heart.)

As a kid, I was prematurely homesick for home too. When I was four I started crying in the middle of a bedtime story. I’d just realized that someday I would be old and my parents would be dead. Who would read to me then? Sometimes when I am reading to my own children, I have to stop and blink my eyes, someday they will get old and I will die. And I know now that no one reads to you once your parents are gone.

Maybe the sorrow subsists at a cellular level.

Being a walking memento mori isn’t fun. And I’ve tried to keep myself from passing a constant awareness of loss to my kids. But they’ve all gone to bed at one point or another crying about the future date when our time together is done. Some inheritances are subject to a kind of strict settlement, I guess. If so, then the sorrow isn’t mine, it’s just something I steward. And my kids will too.

Maybe the sorrow subsists at a cellular level. Intergenerational trauma passed down from foremothers who never got to visit home again after setting sail across the Atlantic. Or maybe I just read them too many poignant picture books about the passage of time. If our family is a compound, time is the catalyst that facilitates our decomposition.

At breakfast last week, Brontë asked me to blow on her too-hot potstickers and then said, “Oh! I wish we could all stay little!” She’s never interested in hearing about the benefits of growing up, so I just said, “Me too.” And then helped cool off her food so she could eat. And I couldn’t help thinking how many mothers in so many homes have done the same thing.

I tried to find a cultural history of People Blowing on Food to Cool it Down but so far my search has come up empty. (If you know where one is, tell me!) But I feel fairly confident that we’ve been blowing on food to cool it down as long as we’ve been heating it up.

Well, we’re really blowing on the air around the food. Hot food releases thermal energy into the air around it, heating up its immediate environment. Energy transfers more slowly between things with similar temperatures. So the heated up air kind of insulates the food, for a short time. The air will lose its heat to the surrounding environment pretty quickly. And so even the hottest food will cool down after a minute or so. No blowing necessary.

Children will not keep forever, but to be kept at all they must be fed. Each bite preserves them for this moment and part of the next.

But for very little kids, a minute and forever are the same thing. “It’s hot! Will you blow on it?” My food cools, usually too much, while I help her. Sometimes I push my breath out over her food because I don’t want to listen to her ask again. But mostly, I do it because I am always anxious for her to commit to taking the first bite of a meal. Once she does, I know she’ll keep eating. Children will not keep forever, but to be kept at all they must be fed. Each bite preserves them for this moment and part of the next.

It’s taken a lot of bites to get us all here, in this moment.

Hominins have been eating cooked food for up to 2 million years. It was a learned behavior. Prometheus gave us fire for light and warmth. But vultures taught us to use it to cook our food. Some scholars think early humans learned to eat cooked food after watching vultures tear into carcasses burned in bush fires. They started eating the charred carcasses too.2 I don’t know if they ate the carcasses while they were hot enough to need a mother’s breath to cool them down. I do know the vultures were on to something.

We will eventually be broken apart by decomposition but we also cannot stay together without it. Digestion is a decomposition reaction, it breaks food down into parts that can be absorbed as nutrients. Mechanical digestion - chewing - breaks food into parts small enough for chemical digestion. Chemical digestion is the part where our digestive enzymes separate the food into absorbable molecules.

Raw food is relatively hard for our digestive system to break down and then absorb. There’s just too many cell structures to chew through. Cooking uses heat to pre-digest food, breaking down enzymes and cell walls. That pre-digestion makes more energy available per bite. It’s possible the increased energy from regularly cooked food was instrumental in developing and sustaining Homo sapiens’ bigger bodies and brains. Cooked food may have helped make us human. Either way, we became accustomed to its taste.

Energy sources and emissions have always been a concern.

Uncontrolled brush fires were too rare and too dangerous to depend on for cooking. So early humans had to learn how to start and then contain fire. Hominins started using controlled fire for cooking at least 800,000 years ago.3 The first hearths were often lined with rock, and placed in the middle of big caves. Energy sources and emissions were a worry then too.

Fuel - wood, coal and bone - took a long time to gather. Fires were difficult to start and maintain. And even if the fire stayed in the hearth, early humans understood the hearth didn’t keep all the danger contained. Smoke could hurt them too. Anthropologists have shown that early humans were very concerned about properly ventilating their homes. A recent study of a prehistoric hearth found that,

early humans were able, with no sensors or simulators, to choose the perfect location for their hearth and manage the cave’s space as early as 170,000 years ago – long before the advent of modern humans in Europe. This ability reflects ingenuity, experience, and planned action, as well as awareness of the health damage caused by smoke exposure. 4

It wasn’t a coincidence. Layers of soot showed the same hearth location was chosen by traveling groups of early humans over hundreds, even thousands, of years.

I imagine the first cooks arranged their food over the hearth-fire with a similar deliberateness. I am not saying that prehistoric cooking methods looked like prep in the Noma kitchen. But food was labor-intensive to acquire, so it would have been handled with care. Some food would have been cooked on stones heated inside the fire, other meals would have been cooked in the hot air just above the flames.

We can imagine how a cave smelled while food cooked because the same chemical reactions still happen in our kitchen when we cook food. A chemical reaction is a transformation, the chemical composition of matter is changed. New textures, tastes and smells are produced. One of my favorite heat-induced transformations is the Maillard reaction,

I am going to let Eric Shulze over at Serious Eats describe it,

The Maillard reaction is responsible for the browned, complex flavors that make bread taste toasty and malty, burgers taste charred, and coffee taste dark and robust. If you plan on cooking tonight, chances are you'll be using the Maillard reaction to transform your raw ingredients into a better sensory experience.

In some foods, the smells produced by the Maillard reaction are a sign of doneness. When you can smell the chocolate chip cookies baking in your oven, they’re done - no temperature probe or timer necessary. That part is simple. But,

…the Maillard reaction is complex. The Maillard reaction is many small, simultaneous chemical reactions that occur when proteins and sugars in and on your food are transformed by heat, producing new flavors, aromas, and colors.

Those new flavors, aromas and colors exist because the chemical reactions have created new molecules. And then when we eat the food, our digestive system breaks up all those new molecules so that we can absorb the bits that will sustain us. Which makes cooking sound more like a spell than almost anything else I can think of, really.

The oldest known cooked food is an 780,000 year old meal featuring carp.5 Cooking the carp didn’t just create new tastes, it also helped preserve it. The right ratio of heat and time extends the shelf-life, or cave-life, of previously raw ingredients. The Maillard reaction produces products that help stop bacteria growth on the surface of food. Cooking meat until well-done kills bacteria below the surface. Rot is slowed, just a little, and contracting a foodborne illness becomes much less likely.

English speakers have been using “well-done” to describe completely cooked meat since at least the 1740s. I think of steak as being well-done, when the outside is charred and the inside is all brown. But it’s a term used for the thorough cooking of any kind of meat.

When chicken is well-done, its juices run clear. I once heard a host of a cooking show say that you can tell when chicken is done by the way it feels when you press on it. If it feels like the meatiest part of your palm, it is still raw. If it feels like two fingers pressed together - I can never remember which two - it is cooked through. This has never been any help to me.

When I try to cook chicken, I press against the bird, press against my palm, press against the chicken, press my fingers together. I can never tell if one feels like the other. So I usually cut into the chicken to see if the juices run clear. Always too soon. Pink juice runs out and down the bird while it continues to cook.

Things don’t go much better when I can find the meat thermometer - which is not often. Afraid of the chicken overcooking, I stick it into the thickest part of the chicken now, a minute from now, 30 seconds from then. Pink liquid flows out from each probe. The chicken is always dry by the time it’s done. It’s past-done.

So when I cook meat, I mostly opt for long, slow braises. With low heat and a long cook, the Maillard reaction can still occur. And I know the meat is done when it falls apart. Pre-digested by heat and time until its soft and safe.

Our ancestors would have developed their own methods for measuring well-done. I don’t know what they were. I don’t even know how they defined done. Done, in cooking and everything else, is an end that’s always changing. Still, I wonder how often a mother like me sat beside the hearth fire, pressing and probing the cooking meat, unsure of how much longer the heat needed to do its transforming, preserving, decomposing work.

When anthropologists first posed the cooking made us human theory, mainstream publications reported on it with something akin to rapture. Fire is cool and cooked food is tasty. But I wonder, a little, where the equally rapturous think pieces are on the other things that sustained us as we became human. And continued to keep us once we were humans, but still too little for big bites.

Maybe the cave babies are just crawling outside the frame.

Not all humans can digest even the most well-done piece of meat or the best fired paleolithic flatbread. Human molars come in between 18 and 24 months. Until then, humans have a hard time with mechanical digestion. Most depictions I see of humans around cave fires feature adults. Maybe, like Brontë, the illustrators think that adults have always been adults. Or maybe the cave babies are just crawling outside the frame. Those babies, like babies now, would have required more nutrients than breast milk can provide.

Now, parents often meet those dietary needs with baby food. But before the development of agriculture and cooking utensil technology, gruels would have been difficult to create. Hominins kept their babies alive the way they did before fire - premastication.6 They’d pre-chew food before feeding it to their young.

Premastication is another kind of pre-digestion. I wonder if humans learned to pre-chew food for their babies from vultures too. Birds are born unable to digest their parents’ diet. Like most birds, vulture parents predigest food for their young, store it in their crop where it turns into a nutrient slurry and then regurgitate the slurry into their babies tiny mouths.

Hominins didn’t digest the food as completely, they’d just break it down in their mouths. But feeding looks similar. The parent chews the piece of food, their saliva introducing digestive enzymes that work alongside, and after, the work of mechanical digestion. Once the food is soft enough, they kiss it into the baby’s mouth.

Many human parents still sustain their babies this way. That’s good. We worry about saliva because it can spread disease. But not all saliva is created equal. Saliva sharing within families is incredibly common and, absent contagious illness, not harmful. Some studies show a mother’s saliva carries even fewer pathogens than her breast milk. And the little saliva passed along with premasticated food has many of the same benefits as breast milk.7

Our prehistory can’t be eradicated by bad philosophy.

A lack of understanding about the nutritional and relational power8 of family saliva-sharing leads some western “experts” to discourage this practice. This discouragement is underwritten by a western philosophical tradition of distrusting women’s bodies. Suspicious of the way a mother can use her body to sustain her children, some think it’s safer for a baby to go hungry than be fed from her mother’s mouth. In many poor communities, baby gruel and food blends are difficult to access. When premastication is discouraged, children in those communities become underfed and more prone to infection.9

Our prehistory can’t be eradicated by bad philosophy. Even in communities where its been long abandoned, premastication exists in another form. Many anthropologists think parent to baby kisses developed because of premastication. Food kisses became kisses. Decomposition is a many-wayed thing. It takes us apart and brings us together.

Like Brontë can see herself in pictures of our early family, I can see myself in the picture of our early human family. I look a lot like the first modern humans, but I look quite a bit like early humans too. The first fires weren’t just for cooking, they were for gathering too.10

Maybe cooking helped make us human, but its the hearth that helped make us feelhuman. Small communities gathered around the fire, telling stories in a language we’ll never know. It’s not so different from my little family gathered around our kitchen table, telling stories that only make sense to us because of our shared history.

Maybe cooking helped make us human, but it is the hearth that helped make us feel human.

If I close my eyes, I can imagine sitting down on the ground, the cave wall against my back. The fire is lit and meat is being cooked. Most of the smoke curls out of the cave, but some lingers. The soot from the fire clings to the cave walls, covering cave art that is already old. The walls are layered with soot and drawings, the way the hearth is layered with soot, bones and seeds. When the cave wall is completely black my community, or another, will paint new scenes.11 It’s easy, maybe, to see each fire as one single blaze and each line drawn as part of one large composition.

There’s a one year old baby in my lap and she’s hungry. I’ll breastfeed her for a few more years, but my milk no longer provides enough nutrients for her growing body and brain. When it’s time to eat, I chew up bites of meat and pulse and then kiss the food into her mouth. When I pause to talk with the woman next to me, my baby grabs my chin to ask for more.

She is still so small, she thinks forever and this minute are the same thing. But I have knowledge that helped transform us from something else to something human. I know we will die and I mourn the inevitability of our breaking apart.12 All I can do is preserve this moment, and maybe part of the next. So I reach for a bit more food. It’s hot but I don’t want her to wait. I blow on it before putting it in my mouth.

Maybe my homesickness isn’t sorrow, maybe it’s love. Maybe it extends back past my Irish mothers and into caves layered with soot.

Maybe Brontë was right when she was very little. Maybe the way we are now is the way we’ve always been. Desperately seeking to find the balance of transformation, preservation and decomposition that will allow us to stay in this minute forever. Always failing, but lighting the fire each night anyways. Maybe my homesickness isn’t the result of sorrow, maybe it’s the product of love. Maybe it was formed long in caves layered by soot, long before my Irish mothers sailed.

My daughters and I will eventually break down into molecules, but those molecules won’t disappear. We did come to be just after the stars. We’re made up of the matter their fires created. And when decomposition can no longer keep us together, when we cannot take one more bite, when we’re transformed into something else…

I hope our love preserves the feeling of being together.

And now, before the eleventy million footnotes, here’s a brief detour into how the Maillard reaction is a perfect example of the scientific field discounting women’s expertise and embracing 20th (and 21st!) century racism

French scientist Louis-Camille Maillard first noted the existence of the Maillard Reaction in 1912. He gave us the temperature at which the reaction occurred, how little water must be present for it to begin and noted when the reaction ended and was replaced with something else - like burning. His big breakthrough was basically “When amino acids and sugars get hot together, they brown.” He wasn’t wrong! It’s nice that he wrote that all down. So the reaction was named after him. His discovery is still celebrated in the town where he made it in France.

But it is a little funny to me, that he gets all this credit when women have been utilizing, and manipulating, the complexity of this chemical reaction since they started cooking food. Only women? No. But overwhelmingly women? Yes.

Sure, we don’t know if women did most of the cooking in Neanderthal communities. But we do know they were already cooking complex dishes - including paleolithic flatbreads made with grass, seeds and pulse.13 And once we move from prehistory to history, we know that in most cultures women have been historically charged with handling the home cooking. (And that even in Ancient Rome, “celebrated professional chef” was an occupation dominated by men.14)

For most of human history, the people cooking didn’t know about molecules or that chemical reactions even existed. But they knew that food could be broken down and built up into different flavors. They knew how to use time and PH levels to achieve different results with the same ingredients.

They lacked thermometers to tell them when the fire had reached 350 degrees. But they knew how hot the fire needed to be and how much fuel it required. They could feel for it by holding their hands beside the fire, above the heating stone or just inside the clay oven. Why wasn’t the reaction named after all of them?

I guess the Homemaker Reaction is a name that would’ve made too many 20th century male scientists nervous.

The real discovery came in 1953. We didn’t know anything about the mechanism behind the reaction until it was discovered by American chemist, John E. Hodge. It’s because of him we know all about the simultaneous chemical reactions and new molecules. His paper describing the mechanism is the most cited paper in American food sciences. Okay, forget the Homemaker Reaction. Why don’t we call it the Maillard Hodge Reaction?

Hodge was a Black man who grew up in a segregated America, he attended segregated elementary and high schools. The fact he has not been given a named credit for his work is straightforward evidence that the sciences are one of the many spaces in America that are still segregated. But it’s also evidence of an American tradition of treating Black people like they exist to support the home, while also denying them the rights (even naming rights) in the home.

Cookery, fuel and stoves continue to be used to enforce that disenfranchisement. And we’ll get into that in this upcoming series that you’ve so generously funded.

Thank you for your support. Let’s keep going.

1 Figueroa, Laura A., and Jack Lienke. “The Dangers of Gas Stove Emissions.” The Emissions in the Kitchen: How the Consumer Product Safety Commission Can Address the Risks of Indoor Air Pollution from Gas Stoves. Institute for Policy Integrity, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep45756.4.

2 Morelli, Federico & Kubicka, Anna Maria & Tryjanowski, Piotr & Nelson, Emma. (2015). The Vulture in the Sky and the Hominin on the Land: Three Million Years of Human–Vulture Interaction. Anthrozoos A Multidisciplinary Journal of The Interactions of People & Animals. 28. 10.1080/08927936.2015.1052279.

3 Hidden signatures of early fire at Evron Quarry (1.0 to 0.8 Mya) Zane Stepka, Ido Azuri https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2891-1514, Liora Kolska Horwitz https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8776-8658, +1 , and Filipe Natalio https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4166-6947 filipe.natalio@weizmann.ac.il Edited by James O’Connell, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; received December 30, 2021; accepted April 25, 2022 June 13, 2022 119 (25) e2123439119 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2123439119

4 The influence of smoke density on hearth location and activity areas at Lower Paleolithic Lazaret Cave, France” by Yafit Kedar, Gil Kedar and Ran Barkai, 27 January 2022, Scientific Reports. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-05517-z

5 Zohar, I., Alperson-Afil, N., Goren-Inbar, N. et al. Evidence for the cooking of fish 780,000 years ago at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 2016–2028 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01910-z

6 Iulia Bădescu, Pascale Sicotte, Aaron A. Sandel, Kelly J. Desruelle, Cassandra Curteanu, David P. Watts, Daniel W. Sellen, Premasticated food transfer by wild chimpanzee mothers with their infants: Effects of maternal parity, infant age and sex, and food properties, Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 143, 2020, 102794, ISSN 0047-2484, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102794.

7 Pelto, G. H., Zhang, Y., & Habicht, J. P. (2010). Premastication: the second arm of infant and young child feeding for health and survival?. Maternal & child nutrition, 6(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00200.x

8 Early concepts of intimacy: Young humans use saliva sharing to infer close relationships ASHLEY J. THOMAS BRANDON WOO DANIEL NETTLE ELIZABETH SPELKE AND REBECCA SAXE, SCIENCE, 20 Jan 2022, Vol 375, Issue 6578 pp. 311-315 DOI: 10.1126/science.abh1054

9 Pelto, G. H., Zhang, Y., & Habicht, J. P. (2010). Premastication: the second arm of infant and young child feeding for health and survival?. Maternal & child nutrition, 6(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00200.x

10 https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/300kya-hearth/ R. Shahack-Gross, F. Berna, P. Karkanas, C. Lemorini, A. Gopher, R. Barkai, Evidence for the repeated use of a central hearth at Middle Pleistocene (300 ky ago) Qesem Cave, Israel, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 44, 2014, Pages 12-21, ISSN 0305-4403, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.11.015.

11 Francisca Moya-Cañoles, Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong, Catalina Venegas, José Cárcamo, Diego Artigas, Rock paintings, soot, and the practice of marking places. A case study in North-Central Chile, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 36, 2021, 102853, ISSN 2352-409X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102853.

12 Pomeroy, E., Bennett, P., Hunt, C., Reynolds, T., Farr, L., Frouin, M., . . . Barker, G. (2020). New Neanderthal remains associated with the ‘flower burial’ at Shanidar Cave. Antiquity,94(373), 11-26. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.207

13 Cooking in caves: Palaeolithic carbonised plant food remains from Franchthi and Shanidar, Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2022

14 Pedar W. Foss, “Kitchens and Dining Rooms at Pompeii: the spatial and social relationship of cooking to eating in the Roman household,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, 1994, 45-56.