First, I am going to tell you about losing my words on NPR when I was interviewed about LDS domestic violence. And then I am going to tell you about losing my words when the LDS missionaries knocked on my door last night. Okay? Okay.

Tuesday

I was a guest on NPR’s On Point last week. It was an episode about domestic violence and Mormonism. I wasn’t going to share it here because I was never able to say quite what I wanted to say.

I am not sure why I had such a hard time finding my words. I’ve done several high profile podcast/radio interviews. And while I am always afraid of saying the wrong thing, I usually get through it without feeling disappointed in myself. But after this interview, I sat in my cold car for a long time. What happened?

I went over what could have gone wrong. A few things seemed like possibilities:

- I got to the PBS studio where I recorded the interview early, but the sound guy was late. I don’t blame him at all. He had to come into work early, before the building’s lights were turned on. I was on time because Riley was able to get the kids ready and off to school on his own. Not everyone has a partner that can take on the morning’s responsibilities - whether those responsibilities involve kids or not. It was very icy outside. I bet his drive into work was miserable. He was still in his coat, breathing heavily from rushing in from the cold, fixing sound issues as the interview was about to begin. I suppose that added to my nerves. But I am perpetually late. If I felt flustered and wordless every time I was rushed, I’d never write or speak again.

- This was my first live interview. I am used to talking about hard things on podcasts and radio shows. But the live aspect left me feeling exposed in a way that surprised me. Live interviews should be, in some ways, less vulnerable experiences than pre-recorded ones. There’s no way for someone to edit and misconstrue your words. But live interviews require quick, direct answers. And while I have a lot of direct things to say about all of this, I am not sure I’ve got any quick ways to say any of it.

Pauses are where I think. I am finding this topic still requires a lot of pauses. During the interview, I felt like every pause cost me a future word. And each lost word was one less thing I said clearly in support of women who need more people saying clear things. After the first few pauses, I think I felt like I’d created a deficit the next answer couldn’t reduce. Which, of course, led to more pauses. - Before you go on a show like On Point, you do a pre-interview with a producer. It’s usually a wide-ranging conversation that helps inform the direction of the show. Some pre-interviews turn into interviews, some don’t. I always enjoy them, either way. You can really pull at all kinds of threads because there is no time limit and there’s no direction yet. Producers are kind of the best, they’re generally very curious and interested in nuance. The pre-interview before this interview was lovely and long.

I know I spend a lot of my time in pauses. So I did try to mitigate that unfortunate tendency with preparation the weekend before the show. But I chose different threads than the interview ended up pulling on. That’s my fault. And it’s one of those times I wish I didn’t do all of this alone. I think a media manager* could have helped me see I was focusing on the wrong bits of the pre-interview deep dive.

*I actually don’t think media managers do that. Who does? No idea. Someone who knows things like that for a living. Whoever that is, I cannot afford their services but could really use them. Obviously.

Ultimately, I am not sure any of those things really account for my stumbling. I think I am just finding I need more than a few minutes to speak clearly through the pain.

The great thing about the show is there were four voices in the conversation. And even on my best day, my voice is by far the least of them.

Meghna Chakrabarti, the host of On Point, is an excellent journalist. She’s curious and direct. One of my favorite combinations.

Jana Riess, a senior columnist for Religion News Service, writes about the Mormon experience with academic rigor and compassionate clarity. She is able to sit in the pews and stand up for the people sitting next to her.

Donna Kelly, an attorney at the Utah Crime Victims Legal Clinic, has spent three decades working on behalf of domestic violence victims in Utah. As she spoke, I just kept thinking, This is a woman I would trust to speak in defense of my daughters, in court and on NPR.

Many of you emailed me after you heard all my pauses on your way to work, while you cleaned the kitchen or in the days after as you caught up on your favorite podcast. You were gracious. Thank you. Maybe it’s okay if our words are stumbling if we just keep saying them as best we can.

I cried when I got this one. Also, can I go by Newsletter Meg in my daily life?

I am still getting emails from people in the Mormon community, telling me about their experiences with domestic violence. I haven’t been able to respond to all of them. Once I do, I’ll probably pause. And then write all the things I wish I’d said on Tuesday.

Whether you take the time to listen to the episode or not, I recommend this from Jana Riess.

Here are my thoughts after the @NPR interview.

— Jana Riess (@janariess) February 1, 2023

Bottom line: the "that's just the action of one rogue man" line of denial misses the point: Mormon culture raised this man, empowered him, & ignored his daughter's cry when she predicted he'd kill her.https://t.co/FnfDQX5xz0 @RNS https://t.co/I9oGsdPrZO

Saturday

Last night, I was in the basement doing laundry when Brontë called down to me, “Mom! There is someone at the door!”

I hadn’t heard the knock. She knows not to open the door on her own, but she was pulling on the handle when I came upstairs. I told her to wait. I looked through the window next to the door. I couldn’t see anyone. But it was dark. And the lights on the street don’t quite reach our front step. I moved her away from the door, “Are you sure you heard a knock?” She was sure.

When I turned on the porch light, I saw she was right. Three LDS missionaries stood side by side across our front steps. Three men - between 18 and 21 years old - who still had the red round cheeks of boys. They’d been hard to see because they were wearing big dark coats. They’d seen me look through the window, so I opened the door. But I might have opened it, anyways. Out of habit. But also out of love. I don’t know how to keep my door closed to my people.

Knock, and the door will be opened for you.

Well, knock and the door will be cracked a little for you. I stood in the sliver of light and asked how I could help.

The one on the left, with the reddest cheeks, said,

“Does Kim still live here?”

Kim is my mom. She moved with us to Denver. When she moved here, her church records moved with her. She would have put my address as her address. Her name is on the rolls of a local congregation. She’s never been in the pews though. Partially because she often works on Sundays. Mostly because the church, always a source of some pain, became unbearable for her in the years after my dad died. She moved into her own place by the end of our first year in Denver. Her inactivity plus her move make her what the LDS Church calls a lost member.

A lost member is someone who is on an LDS congregation’s rolls but does not attend church and no longer lives at the last known address. When a lost member is found, they’re invited back to church. Whether they accept the invite or not, they become unlost once their address is added to the space next to their name in the church records. I am not a lost member, because the church knows where I live.

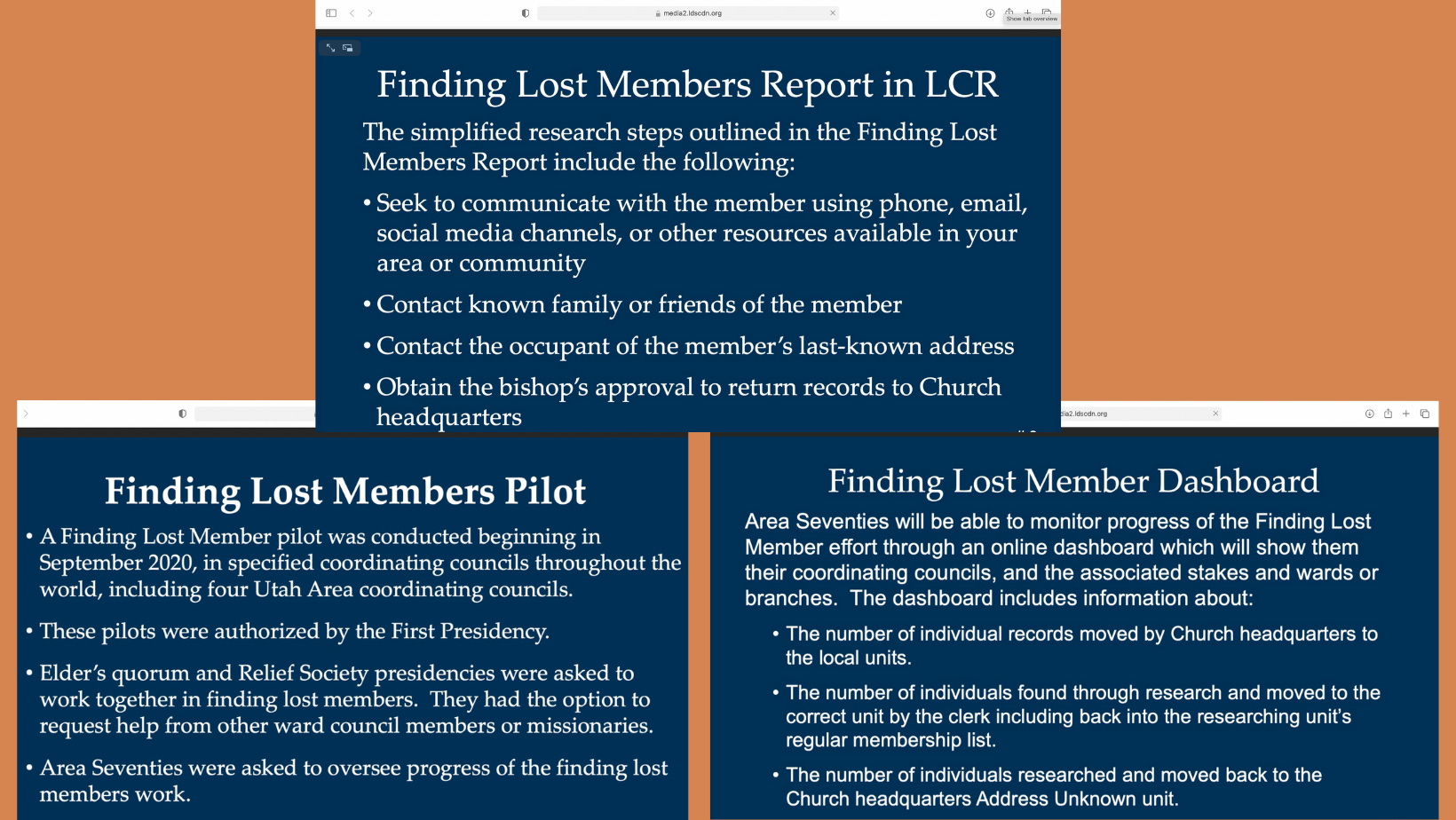

The LDS Church has always tried to find “lost members,” and they’ve often used missionaries to do it. But they’ve recently developed and implemented a new Finding Lost Members Program with “simplified research steps:”

- Seek to communicate with the member using phone, email, social media channels, or other resources available in your area or community.

- Contact known family members or friends of the member

- Contact the occupant of the member's last-known address.

My mom doesn’t use social media or answer unknown numbers. Her four children are her only known family members. Three of the four of us no longer attend church. And the one who does (and who is the best of us, really) is no narc. So I guess the missionaries were on simplified step three when they knocked on my door.

“Does Kim still live here?”

There was a pause, but it didn’t help me think. I couldn’t find any words except, “No, she doesn’t.” I hope I smiled when I closed the door. But I can’t remember closing the door.

Riley found me upstairs, curled up on the floor of Viola’s room. I knew he was there when I felt his palm on the back of my neck. I didn’t know I was shaking until I felt his steady hand.

“Meggi?”

I whispered, “The missionaries were just here.”

He started to get up. To go outside and find them. To tell them he was a missionary once too, he loves them, and he hopes they stay safe and well. But please, don’t knock on our door again. But I held his hand against the back of my neck and he settled down next to me. He waited for me to find the words.

“I thought I was upset because they represent the Church and the Church,” and here I waved my hands to encompass the patriarchal power structure, anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric, White Jesus, Smaug-like treasure hoarding and everything else, “can hurt our family. But it’s not that. That’s not what I saw when I opened the door. I saw three young men I could’ve known when they were little boys.”

I could see their mothers holding them as babies. Swaying back and forth in the halls of church, while they talked to other women. Sometimes one of the older women reaches for a baby, holding him on her hip to give his mother a rest.

I could see their mothers getting them dressed for church every sunday. Dabbing a wet cloth across a smudge on their little white shirts as they hurry out the door.

I could see them coloring pictures in primary, kneeling on the floor so they could use the seat of their little metal chair as a desk. Sometimes one of them scribbles off the page and onto the seat, accidentally on purpose, to see if crayon draws on metal.

I could see them growing up, doubting and believing. Hanging out in the church halls until someone asks why they’re not in Sunday School. Sometimes one of them stays in the hall, accidentally on purpose, to see if anyone notices.

I could see them deciding to go on missions, two years spent bringing people to God. I could see them in prayer, begging each day to bring them closer to God too.

I could see their mothers in prayer too. Praying for their sons to know God’s love and to come home safely.

“Years ago, I would have asked those boys to come in from the cold. I’d have made them hot chocolate. And while I asked them about their hometowns, I’d have taken down their mom’s numbers, so I could text them photos of their sons, safe at my table. But even though I could see them, I couldn’t invite them in.”

I’m still in the pause that followed. It’s full of grief.

I’ll never sway back and forth in those church halls again. I cannot easily reach for those babies to give their mothers a rest. And when I try, I think it feels like a threat instead the relief I’m offering. Most of the women don’t reach for my babies anymore, either. Even the ones who once knew the weight of holding them. I am not sure I can blame any of us. Our arms are already so full.

Well, no one reaches for your babies until they’re officially lost. And then it’s a different kind of reach, and it feels more like a threat than a relief.

I don’t know if this is just how community works, or if this is just how community fails.

Maybe the next time missionaries knock on our door, I’ll be able to invite them in for a little rest from the cold. I won’t try to talk them in or out of anything. I’ll just ask them about their families, what they like to do, what they hope to do. They’ll ask if they can teach us about the church. We’ll decline but make sure they leave with some food.

Maybe I’ll be able to close the door with a smile.

But right now, I’m still on the floor with Riley’s hand on my neck.