This is a Pocket Note. This is where I follow Mary Oliver's Instructions for Living a Life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it. Each newsletter is a simple model for paying attention and cultivating shared meaning.

Pocket Observatory is not-for-profit project offered to you for free through a Creative Commons license. The continuation of this work depends on support from people like you.

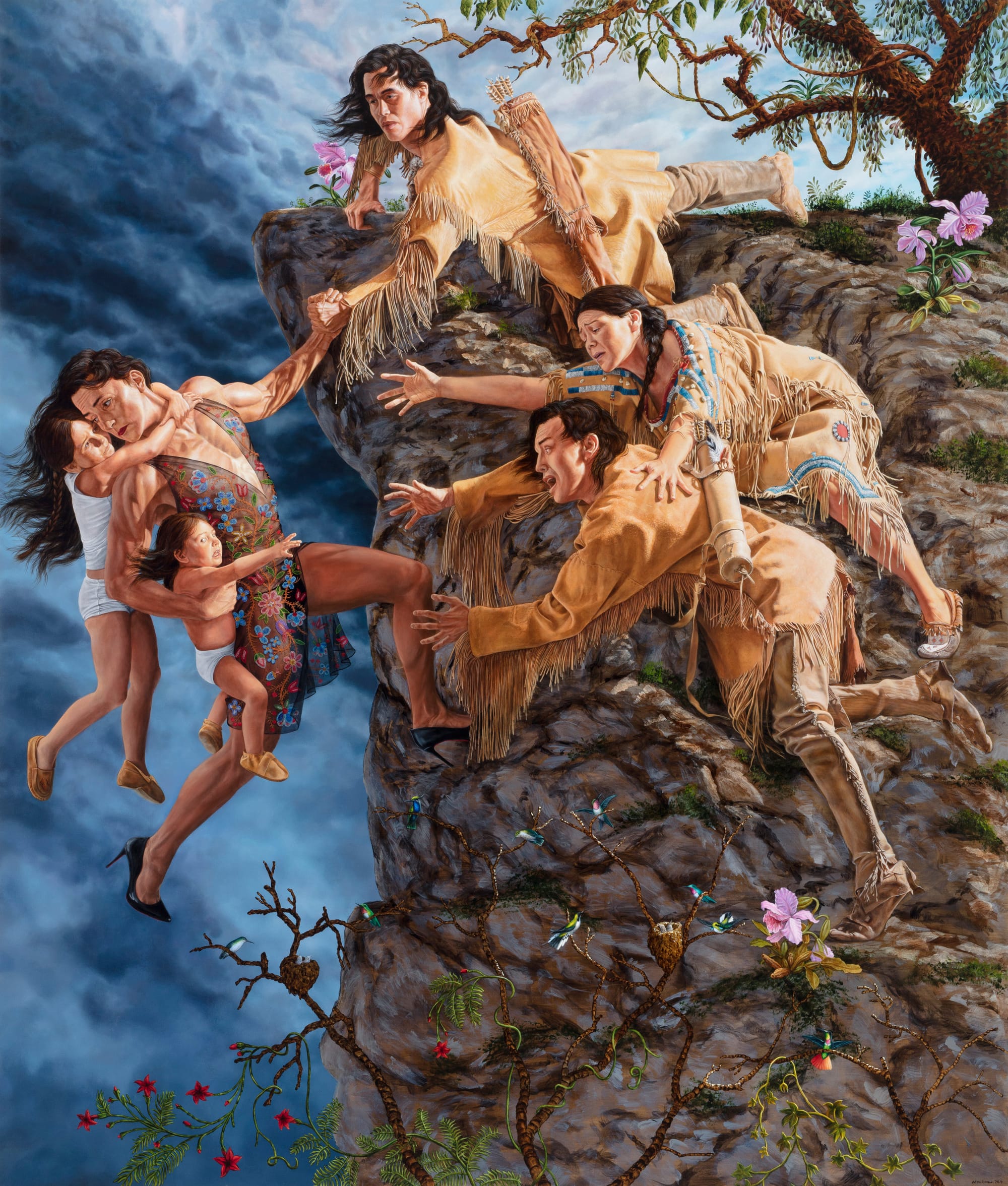

On Saturday, we took our kids to the Denver Art Museum. I was anxious to see the new Kent Monkman exhibit. Monkman is an interdisciplinary Cree visual artist and member of Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 Territory (Manitoba, Canada). History is Painted by the Victors is his first major show in the United States.

Here is a brief excerpt from the exhibition guide about Monkman's body of work:

Kent Monkman (ocêkwi sîpiy/Fisher River Cree Nation in Manitoba, actively working in Toronto and New York) brings history firmly into the present, using sly humor and flair to look critically at the stories that shape our society. He draws visual inspiration from past artistic styles to create a new version of history painting. Through detailed, dramatic, and often humorous compositions and monumental canvases, Monkman immerses viewers in scenes that depict marginalized histories and suggests ways to create conditions for genuine healing.

Monkman illuminates the histories, identities, and realities often missing from dominant narratives, particularly those of Indigenous and queer communities. The epic scope of Monkman’s paintings moves through searing scenes of oppression, lament, humor, pride, and celebration. Through allegory, metaphor, and cunning art historical citations, his works challenge the authority and authorship of official colonial histories that many have learned and perpetuated.

By centering Indigenous and queer perspectives on North American history within the frame, Kent Monkman offers new ways of seeing our shared histories, the present, and approaching futures.

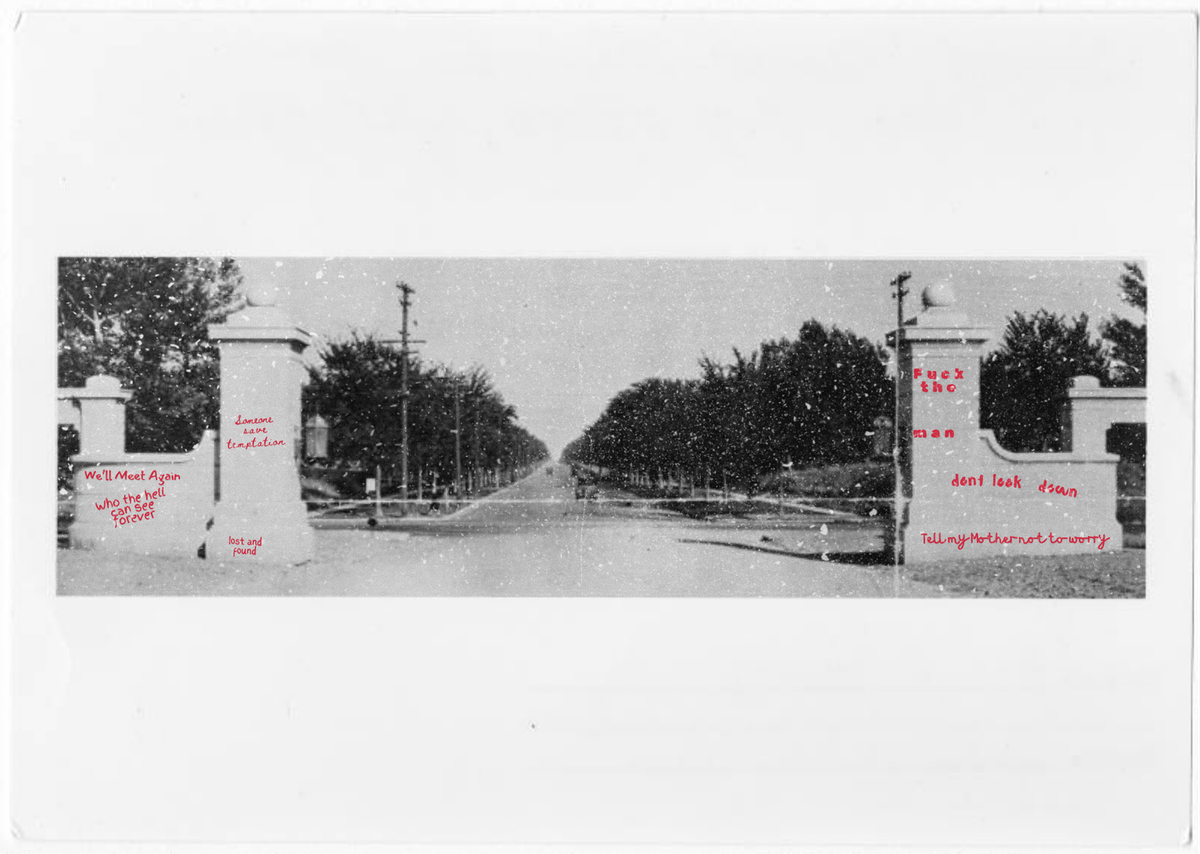

A woman standing at the door took our tickets. She looked down at my seven-year-old daughter. And then gestured to the words written across the glass doors to the exhibit,

This exhibition contains depictions of violence and nudity. Parents and guardians may want to preview.

"I just wanted you to be aware there are depictions of violence and nudity. I am not at all telling you not to take her in there. I just needed to make sure you knew because …”

She paused. And here I knew I could never do her job. Because every time a family with a seven-year-old came into the line, instead of pausing I’d start talking a little too quickly,

...because I don’t know what your child can handle. But also no one asked Indigenous children if they could handle being abducted from their families. And whether your child sees this artwork or not, they are living in a reality framed by the attempted genocide of Indigenous Peoples of North America. You want to keep your child from seeing representations of the violence that built their world. Why? Is the answer worthy of you, of your child?

Can I ask you to consider that there are other possible realities? And that art can help us consider them? And once we consider them we can construct them?

Here is just one example: Kent Monkman paints historical interventions like The Deluge, a piece where children who were once swept away by church and state atrocities are now rescued. When you sit in front of The Deluge, you’re witnessing a reality framed by the protection of Indigenous children. How can your child help construct that reality if they've never considered it? How can they consider it without art like this?

Of course, this is very difficult to convey to a child. I know that. A child looking at a painting like The Deluge will want to know if the children were really rescued. And you’ll have to tell them that some were rescued, but many weren’t. You’ll have to explain that people died trying to rescue the children. You’ll have to tell your child about state violence. You’ll have to tell them that state violence is still used against Indigenous people, including children. You will have to help them see things as they are now.

History is Painted by the Victors depicts the abhorrent nature of state violence. The United States government targets children with propaganda that glorifies state violence. The White House posts videos of people in shackles and calls it ASMR. The President of the United States shows children bloody images of himself on Easter. First image link. Second image link.

I know that sounds scary. But your kid will be all right. The thing is, many children do not go to an art exhibit to learn about family separation and other kinds of state violence. They learn about state violence through their own life experiences. Asking your child to look at a few paintings is not asking too much of them or yourself.

Anyway, I am not here to tell you what to do one way or another. But I think you should go in. So I guess I am here to tell you what to do.

The woman who took our tickets was more succinct. After her pause she just said, “...not everyone notices the sign.”

See? I could never do her job. I thanked her for her care and we walked into the exhibit. I looked back at the warning through the glass,

.weiverp ot tnaw yam snaidraug dna stneraP .ytidun dna ecneloiv fo snoitciped sniatnoc noitibihxe sihT

I bent down to my daughter,

“Hey, are people naked in real life a lot of the time?” She nodded.

“Okay, and do people hurt other people and get hurt in real life?” She nodded her head again.

“Okay, art is about real life and so sometimes art has depictions of naked people. You already knew that. But in this exhibit, sometimes there are paintings of people that are hurt or hurting others. It’s not gory or gross, but it is upsetting. We’ll talk about what it means as we go through, okay? And if any of it makes you too upset, we’ll leave. There is even a special room at the end of the exhibit for people who just need to feel protected and calm. We can go that room and talk anytime you want. Deal?”

She nodded once more. Deal. And then we turned to look at the first painting.

The paintings we considered together

Genocide is a primary division of oppression that contains legions of distinct forms of violence. Resistance is a primary branch of hope that contains an ever-unfurling array of liberation. Monkman works at a scale large enough represent both systems.

An exhibit of Monkman's work can feel overwhelming, especially for someone who is very young. So I tried to help my youngest focus on a thread she could understand - Monkman's depictions of Indigenous children who were abducted from their families and forced into residential schools.

Monkman collapses time and space to dramatically tell the history of more than 100 years of forced removal of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children from their families and communities by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, United, and Presbyterian churches. The experience of tens of thousands of Indigenous children within hundreds of residential schools in Canada and boarding schools in the US was shattering and horrific. The language loss, cultural isolation, mentorship disruption, intergenerational trauma, and more are still felt today. - Kent Monkman: History is Painted by the Victors Exhibition Guide

An Indigenous child reaches for a bird perched on a windowsill, just out of reach—as were the freedoms to move, think, speak, and be Indigenous. This work presents a stark and haunting representation of the cold loneliness of Indigenous children in boarding schools, yet it also honors the hope and resilience of those children, now Elders, who survived and became knowledge keepers. The Sparrow poignantly calls for truth-telling and repair far beyond the European drive to possess and hoard. - Kent Monkman: History is Painted by the Victors Exhibition Guide

The Deluge speaks directly to those who have experienced the boarding school system and recognizes their pain. With the help of Ancestors, Miss Chief rescues Indigenous children from the allegorical flood of displacement by settler cultures and returns them to their families. It is a testament to true leadership of those who fought for the children’s return and continue the fight to uncover the true extent of the atrocities experienced and return the protection of children to the authority of Indigenous nations. - Kent Monkman: History is Painted by the Victors Exhibition Guide

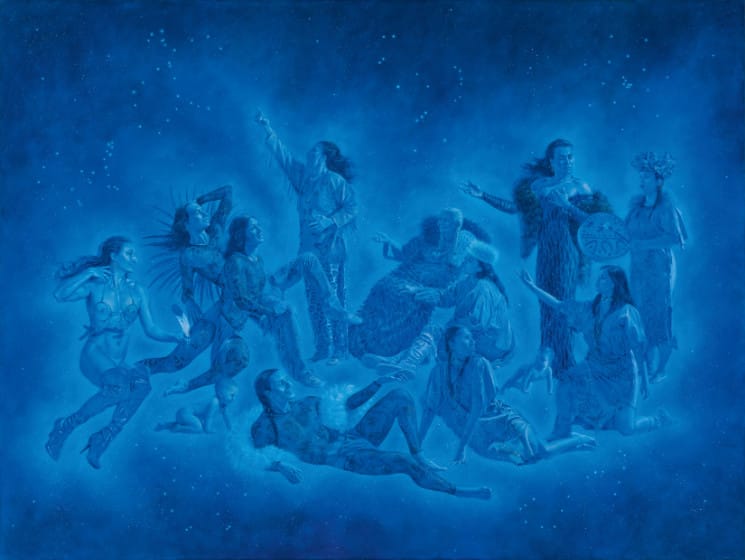

In this scene, multiple generations of Ancestors gather in the spirit world. Miss Chief, holding a sacred eagle feather, reminds us of the time-bending, relational, and intergenerational nature of our connections within kinship constellations. - Kent Monkman: History is Painted by the Victors Exhibition Guide

Related Reading

Pocket Observatory is not-for-profit project offered to you for free through a Creative Commons license. It is run by person - me! The continuation of this work depends on donations from people like you.

Give a one-time donation. A few examples of how your donations help me work: $3 buys me a pen! $25 buys me paper for a month! $90 buys me three hours of childcare!

Give an annual recurring donation. Join a community of fellow observers. Benefits include commenting ability, snail mail and virtual community meetings.