I've Slept with my Baby Blankie for 36 Years

I could be embarrassed about my baby blanket. Instead, I'll tell you everything it's taught me.

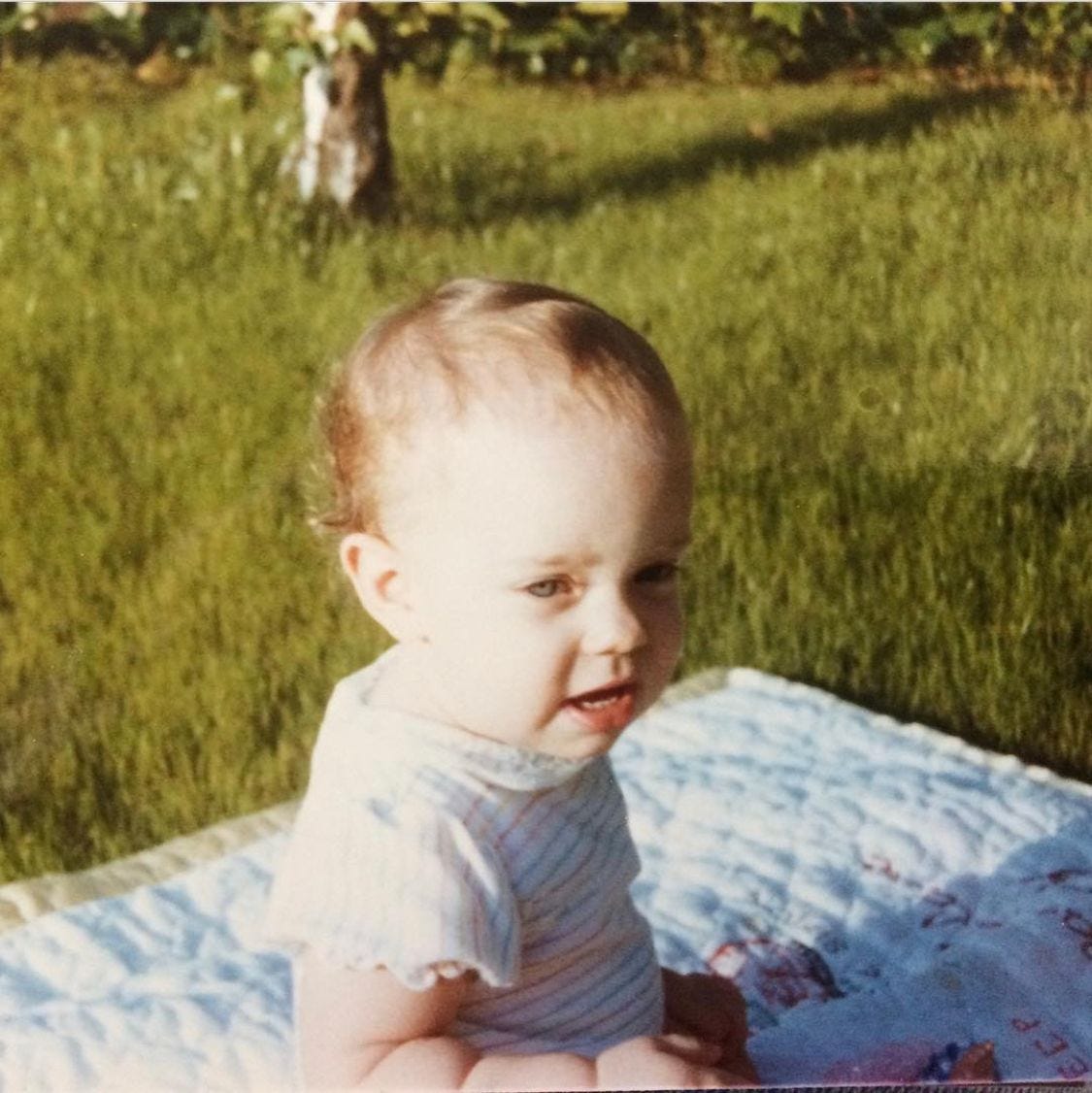

I am thirty-six years old. I sleep with my baby blanket every night. I am not actually sure that my blanket and I can exist apart from one another. I mean, we probably can? If I were to leave this world, I suppose my blanket would remain. If my blankie were thrown in a fire, I guess I’d still be here. (I had a hard time even writing a metaphorical fire for my blankie just then.) My continued existence can’t possibly be tied to the continued existence of my blankie. But I’ve got no real proof that it is not. We’ve never not had each other.

Sometimes, if I am being honest, I think of my blanket as she or them instead of it.

See what I did in that first paragraph? I fell into anthropomorphic thinking. I attributed human behavior to a non-human, non-living thing. It’s a thing that toddlers do with baby blankets and stuffed animals. I do it too, with my blankie. Mostly, now in adulthood, as a winking joke. But sometimes, if I am being honest, I think of my blanket as she or them instead of it.

A psychiatrist in the 1950s said that when a baby is still a baby, they realize they are themselves and their mother is not a part of them. This separation is traumatic and so they choose a transitional object, a blankie or stuffed animal usually, to help them adapt to being an unconnected self. Toddlers treat their blankies like a person because they are newly aware they are completely alone. The blankie-as-person helps them feel less alone. I guess I still need my blankie because I am never not aware I am alone. Or maybe, more precisely, I am newly aware of being alone all the time.

Transitional objects aren’t just used by babies. People who are neurodiverse,children and adults, often find transitional objects to be a therapeutic good. That makes sense to this neurodiverse writer. Children who suffer trauma and loss often get comfort from transitional objects. The blankies and stuffed animals provide an accepting stability, they can handle every emotion. Adults use them because of this too.

These objects can be touched and held, lessening the feeling of isolation. Funny things about transitional objects. Their existence might be super culture dependent. Old studies show that cultures where the child is more likely to be separated from the mother produce more children with transitional objects. There seems to be a rural urban transitional object divide, at least there was in Italy. Rural Italian children were much less likely to have a transitional object than urban Italian children.

I guess that my daughters left that first liminal space of new aloneness. And I guess I never have.

I am not sure how much the limited data represents reality. My own urban children were always around their mother, mostly because we couldn’t afford childcare or preschool. Only one of them developed a relationship with a transitional object. She grew out of it around four years old.

Most therapists don’t fret about kids having a personified blankie or teddy. Children naturally let them go when it’s time. That’s why they’re called “transitional”, they are only needed for liminal spaces. Once a child has left an in-between, they tend to leave the blankie or stuffy too. I guess that my daughters left that first liminal space of new aloneness. And I guess I never have. The girls view my blankie with bemusement. I just say I’ve never stopped needing it, shrug my shoulders and then snuggle into my blankie. Well, what remains of it.

The binding has been rubbed away from the top half of the blanket. The fabric on either side is threadbare. There are some holes where batting sticks out. Or maybe there are some places that aren’t yet holes. I have a hard time sleeping without it. My blanket went to college with me. When I had each of my three babies, I debated over bringing blankie to the hospital with me. I chose not to, because I didn’t want to get any blood on it. Blood has been washed out of it in the past though. So maybe I didn’t need to worry.

This last summer, my family went away for a month because my husband had a sabbatical. I couldn’t fit blankie in our limited luggage. I left her behind. It was the longest separation we’ve ever had. I woke up in the middle of most nights reaching for it. When we got home, I went up to my room and held the satin edges to my face.

I am not sure how many more washings my blanket can withstand. The other day I thought about freezing it instead of washing it. You know, like people do with very nice jeans they don’t want to put in the washing machine. (Which makes me wonder...where are rich people de-stinking their jeans if they no longer have freezers?)

My baby blanket isn’t really a blanket. There is a difference between blankets, quilts, duvets, coverlets, bedspreads and sheets. Did you know “blanket” comes from the name of the Flemish fellow who made one on a loom in the 1300s? His name was Thomas Blanket. Good old Tom Blanket. A couple of hundred years later, Shakespeare was the first person to use “blanket” as a verb. In King Lear, Edgar talks about how he’ll disguise himself as a beggar,

My face I’ll grime with filth, blanket my loins, elf all my hair in knots.

I wonder how Shakespeare would use Conley as a verb? Given my contributions to humanity so far, “conley” might just be one of those non-action verbs, a state of being. Maybe something like “sitting with inherent intention." Sounds like a lot but isn’t much, you know?

Anyways, even though I blanket myself in my blankie, it’s really a quilt. My baby blanket is whole cloth quilt, which just means it’s made without patchwork. When my quilt was new, the bottom piece of fabric was yellow and the top was white. The white fabric was embroidered with characters from nursery rhymes, Little Boy Blue, Jack and Jill, Little Miss Muffet and her spider. The batting in between the two was thick. And the whole confection was bound up with yellow satin.

Quilts have quite a layered history. (See what I did there?) Quilted floor covers are depicted in Ancient Egyptian art. In Medieval Europe, quilting was used to make clothing. Its construction made it light and warm. The multiple layers provided padding under armor, protecting wearers from chafing. And for those who could not afford armor, a top layer of quilted clothing provided some protection from pointed things, like knives, arrows, spears and swords. A quilt as a protective layer makes sense to me, I’ve always felt protected by mine. Quilts need a quilter and mine had a good one.

My grandma, Margaret Conley, made my baby blanket. I was her second son’s first child. She sewed and embroidered the blanket in the New Mexico house where my dad spent most of his growing up years. I remember that house, a little. It sat on a short street in a small unincorporated town called Mesilla Park. There was a tree in front of the house and a pool in back. Although, by the time I was around, the pool was always drained. My family lived in California and we visited my grandparents when we could afford to, which wasn’t often enough.

Quilts need a quilter and mine had a good one.

We drove from California to New Mexico for Christmas one year. The back of our Isuzu Trooper was full of presents hidden by draped blankets. My blanket was on my lap, it’s yellow fabric and satin worn through by my worrying fingers. My Aunt Nancy promised she’d fix it when we got to New Mexico. I was happy about the blanket and I was worried about Santa. What if he couldn’t find us? My dad was happy to be going home and worried it was going to be his dad’s last Christmas. It was.

My grandpa was already dying of cancer by the time I was born. He died before I knew the death of loved ones existed outside of fairytales. Still, I remember him in that house. I know the garage of my grandparents house was big enough for my grandpa and me to make a little boat together. And I remember my grandmother’s bed was big enough to fit her, me and my Grandpa. He’d been sick for a little while, she’d been sick since she was born. She often had to lay down. I only remember climbing into their bed once. It was on that Christmas trip. My Aunt Nancy had taken my blankie and fixed it, replacing all the worn yellow fabric and worn yellow satin with bright pink fabric, bright pink satin.

I don’t remember my aunt handing me my restored blanket. I do remember having it in my hands as I ran back to my grandma’s room to show her. My grandparents had two poodles. I tripped over one in the hall as I ran. My stomach fell at the same time I did. I couldn’t look back, I was certain I must have killed that dog. I got up and kept running with my blanket, my feet now faster with fear than excitement. When I got to my grandparent's bedroom door, I shouted, “LOOK!” and held the blanket high above my head. They both laughed and waved me into bed with them.

They would both be gone within the next three years. But I didn’t know that then. I just knew everything was warm and my blanket was soft.

I climbed under the bedcover. I was happy with these people I did not see often very often, who seemed to want me anyways. Even at five, I knew that was special. Smoothing out the stiff newness of the satin binding with both my hands, I worried about the dog I’d certainly left dead the hall. Would they still want me after I’d killed their dog? When I think of the purest form of relief, I remember how I felt when that damn dog wandered into the room. Just a few moments behind me, and definitely not dead. My grandparents lifted blankie so it spread out across us and they admired each new stitch. They would both be gone within the next three years. But I didn’t know that then. I just knew everything was warm and my blanket was soft.

The home my grandmother made was warm, the one she grew up in was cold. She was born in a New Mexico mining town in 1929. Her mother neglected her. Her father paid enough attention to hurt her, apologize and then hurt her again. Things got worse when her parents divorced in 1937. Margaret was bright, a writer and thinker. She didn’t get to go to school beyond the 8th grade. By 12, she’d been sent to work in another family’s house for room and board. She got married at 15, pushed by her mother who wanted her to leave home permanently. Margaret got pregnant immediately and her husband left almost as quickly. The marriage was annulled because his family disapproved of his low class child bride.

Margaret had the baby a month after she turned sixteen. The father did not want to even know the child’s name. There was another marriage in her teens, which was bad. And two more babies, who were good. Her second marriage ended. She met my grandpa and married him when she was in her twenties. They raised those first three babies and had two more. My dad was one of the two, who were two of the five. The family was lovingly stitched together to make a whole.

My grandmother forgave her parents. But I never have. It’s funny how easy it is to hate people you’ve never met. I guess my hate connects me to them like my love connects me to her.

My grandmother forgave her parents. But I never have. It’s funny how easy it is to hate people you’ve never met. I guess my hate connects me to them like my love connects me to her. Margaret was always ill, she was born sick. When she was baby she was so small, her mother kept her in a shoebox. Maybe a family story, maybe true. The least believable part to me is the part where her mother thought about her enough to put her anywhere at all. Some of my grandmother’s ill-health was inflicted on her. Indifferent company town doctors caused permanent damage to her lungs with careless childhood cures.

As a child, one of Margaret's hands got caught in the wringer of a #3 wash tub. As she pushed the clothes into the wringer, she pushed too far and the wringer froze around her hand. She couldn’t move it forward or backward. She didn’t tell anyone how she got her hand out, but the long scar on the inside of her hand proved her pain. I don’t know if her hand still hurt when she made my baby blanket in the 1980s. Sometimes old aches surface when we are doing something new. Although, really. She was doing something older than her hurt, wasn’t she? She was working with a needle and a thread.

How old is that work? We don’t know. We are not sure how long women have been using needles and thread, or how long they’ve been weaving cloth. What we know about the history of textiles depends on what has been preserved. Any piece of fabric that is not actively preserved will disintegrate. And so thousands of years of the traditional work of women is work we cannot witness. Arid climates, like those in the Middle East, parts of China and much of South America, preserve cloth well. As do the peat bogs that dot much of Europe. Some kinds of coffins preserve cloth, and so do some kinds of caves. Permafrost preserves material woven from fibers as well as viruses and wooly mammoth carcasses. Which makes my freezer idea for my blankie seem less silly.

String is a tool and it had to be invented.

We take string and her daughter, thread, for granted. But we shouldn’t. String is a tool and it had to be invented. A string is made by twisting fibers together to make many weak fibers into a strong thread. The fibers can come from plants, like cotton and flax. Or from animals, like wool. Or the cocoon of the larva of the ombyx mori moth, like silk. Neolithic cultures across the world invented string independently. Different threads, different people, different places.

There’s rarely recognition for technology that mends, I suppose.

The Neolithic Era is the last bit of the Stone Age, right before we hit the Bronze Age. In Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Elizabeth Wayland Barber argued that if we were really naming epochs after their most impactful inventions, we’d have named the Neolithic Era, “the String Revolution”. The Thread Age never should have been lumped in with The Stone Age. It deserves it’s own epoch. We’ve never respected soft power, so thread and woven cloth never make it into our discussions of leaps in pre-historic technology. The Ages go from Stone to Bronze to Iron. All technologies made to break apart rocks, trees, and skulls. There’s rarely recognition for technology that mends, I suppose.

String led to thread and then to yarn and then to textiles. Humans were weaving cloth from spun fibers at least 20,000 years ago on warp-weighted looms. A warp-weighted loom is a simple tool for a long process. It stands upright, with warp threads hanging down with weights tied at their ends. The weaver walks back and forth weaving in the weft. When the loom is very wide, two weavers can work. The weavers were generally women, moving back and forth, back and forth. Women pacing with babies, women pacing with weaving, women pacing with women. These types of looms were still in regular use in isolated parts of Scandinavia until the 1950s.

The technology of textiles is old, but it didn’t become affordable for millenia upon millenia. It simply did not scale well. The natural and human resources required were costly. The plants and animals that provided the fibers had to be raised and harvested. There was the labor of women to spin the fibers into thread, first just by hand and then with a spinning wheel. Once the thread was spun, the weaving could start. A loom and the labor of more women to weave. And then the work required to stitch and sew all that cloth into something newly whole. A single piece of the fine flax linen ancient Egypt royalty slept on required years of production from seed to sew. The same can be said of Viking sails and medieval tapestries woven with gold thread.

Who made the fabric that makes my blankie? Did they have enough to keep warm themselves?

Historically, very few people had more than one or two sturdy pieces of woven clothing. The average person didn’t have woven bedding for most of our prehistory and history. They kept warm sleeping in bed together, or with livestock and sometimes they didn’t keep warm at all. People didn’t start sleeping with woven coverings until the early modern period. And even then, bedding was so valuable it was often left to other family members in wills. We think of babies and blankets as belonging together, but a baby blanket for each baby is a relatively new luxury. My grandma just drove across Las Cruces to a fabric store to get the cloth that made my blanket. Who made the fabric that makes my blankie? Did they have enough to keep warm themselves?

As cloth became more widely available, women began to tell stories with it. My grandmother told the story of her love for me with an embroidered quilt. Quilts have carried stories for centuries across cultures. Harriet Powers is one of the great storytellers in the American quilt tradition. Two of her story quilts are known to have survived, Bible Quilt 1886 and Pictorial Quilt 1898. Both contain sequences of biblical and astronomical stories worked out in appliqué, a technique traced to Benin, West Africa.

Enslaved at birth, Powers became an exhibiting artist and landowner after the Civil War. A white woman asked to purchase Bible Quilt after she saw it in an exhibition. Powers said it was not for sale. She knew her work was priceless. Later, after great financial stress, Powers took the quilt to the woman and said she’d sell it for ten dollars. The woman offered five. At the urging of her husband, Harriet Powers accepted the price. There’s something uniquely terrible about our American history that made keeping a blanket already made too expensive. We know Harriet Powers made other quilts with other stories, but we don’t know if they have been preserved.

The stories on my quilt rubbed away years ago. My grandma embroidered the figures from nursery rhymes with red, blue, yellow, green, brown, and black threads. Now just a few clumps of thread remain. A red line that was once a mouth, with two little light blue knots above that were eyes. A broken line of brown embroidery here, a bit of dark blue there. Her work was neat and looked hand-drawn. Like she was illustrating a children’s book with string.

Embroidery is nearly as old as thread. There’s evidence for embroidery in China going back to the Neolithic age. In Sweden, a bog preserved garment from 300 CE is worked with embroidery. The first known embroidery sampler, an example of needlework, is from the Nazca in Peru. It’s dated to 300 BCE. It’s a piece of cotton embroidered with 74 images of flora, fauna and mythological creatures. Samplers were originally used to demonstrate artisan skill and record patterns.

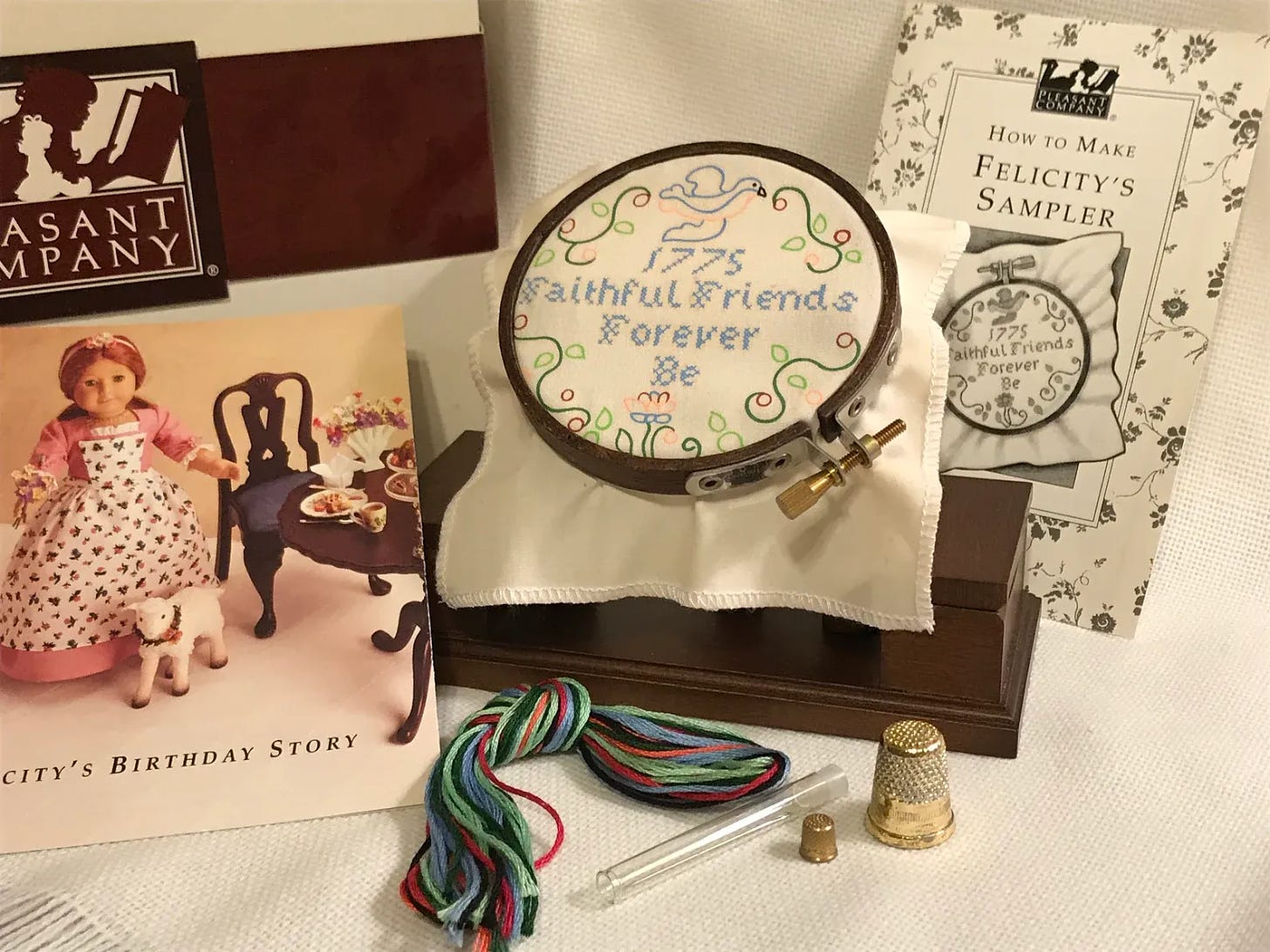

By the late 1700s, samplers in America were mostly used as an educational tool for girls. Samplers made their way into some 90s girls bedrooms because of American Girl Dolls. I know about embroidery samplers because of my American Girl Doll, Felicity. In the American Girl books, she loathed having to sit and stitch out proof of her needlework skills.

Sampler work was supposed to keep girls still and their hands full. Often they embroidered religious messages so that their still fullness also included godliness. The pieces they stitched could be complex and the legacy of those pieces is complex too. Many of those young girls are only known to us because they stitched their names onto their sampler.

The samplers are often rote, but surely the girls who stitched them were not. I sometimes wonder how much of themselves remains in the thread they worked their names in. A tear long dried or a bit of spit from trying to tame the thread with their tongue. Some girls left their names in thread but other girls lost theirs in it. Quilts and needlework can tell stories; they’ve also been used to erase them. American residential schools used needles to pierce instead of mend. The schools included American-style quilting and embroidery in their curriculum of cultural genocide.

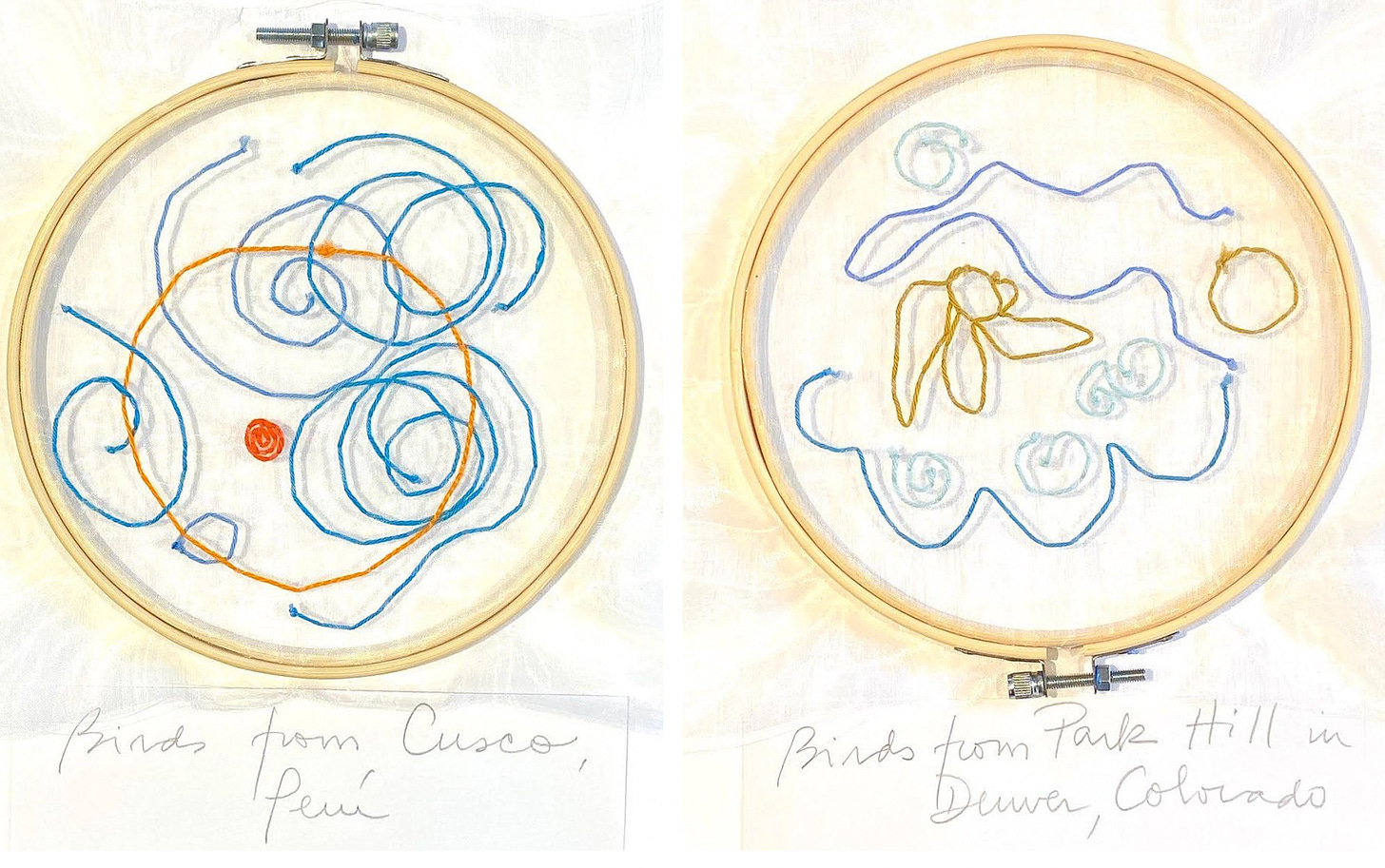

Ana Maria Hernando is an artist working in cotton,tulle and thread to reclaim a soft power she calls, “big, feminine, unstoppable—in size and color. Unconstrained, unapologetic.” Last week, I walked through an exhibition of her art at the Denver Botanic Gardens. The walls were lined with Écoutons, pieces of embroidery worked while listening to the song of birds.They’re a form of “visual translation”. The stringing song of the birds from my neighborhood, Park Hill, Denver sit next to the threads of birds from Cusco, Peru. The embroidery will last longer than the song of the birds. But only a bit longer, each one a brief pricks in the fabric of time. There’s a power in their shared fragility.

Maybe my last memory of her voice disintegrated along with a thread from my blanket.

What was my Grandma listening for as she embroidered my baby blanket? Did she do her needlework while listening to Dolly sing? Or while watching TV with my grandpa? Did she sew in silence listening for sounds long faded? The memory of her grown son’s childhood laught, how did he sound when he was wrapped up in own blanket? Or did she listen for waves that hadn’t begun vibrating yet, sounds of the future? Could she hear that the echoes of her life stopped bouncing back from just a few years ahead? Did she listen for my voice? Could she hear how she’d shape it even though I cannot, I cannot, I cannot remember the sound of hers? Maybe my last memory of her voice disintegrated along with a thread from my blanket. Maybe everything is tied together.

The oldest known fibers used to make string don’t exist anymore. Well, they exist. But we can’t see them on our own. They were found in a cave in the Republic of Georgia. Made of flax, some of the fibers had been twisted for string, others had been dyed. I wonder if some of them were yellow, if some of them were pink. We can only see them now with a microscope. Archaeologists happened upon them when sorting through the clay on the floor of the cave. They weren’t looking for the threads. We so rarely are. The fibers are 34,000 years old. Maybe the threads my grandma worked aren’t mostly gone, maybe I just can’t see them.

34,000 years old is old, but those aren’t really the oldest known threads. There are some older still. When the center of all things got hot enough to expand and create the universe, the energy made a web. Truly! A cosmic web that is the warp and weft of existence. We can’t see it on our own. We need a spectrograph. Each thread is made of dark matter and gas. The galaxies of our universe formed along the threads, pulled together by the gravity that lines each cosmic filament. If the web hadn’t been worked into the fabric of space, we’d never have gone from gas to dust to life.

Sometimes the things that first held us, the first things we held, can’t bear the tension of our expansion.

The cosmic threads are beautiful and they will not last. As the universe continues to expand, the threads are being pulled apart. They’re disintegrating, like the threads on the floor of a cave, like the threads in a blanket. I guess the threads of my blanket have pulled apart as I've grown too. Sometimes the things that first held us, the first things we held, can’t bear the tension of our expansion.

Funny thing about the cosmic web? Even with the right instruments, we can only see it through the great distance of many light years. When we see the cosmic web now, we see the threads of our creation as they were eleven billion years ago. All the way back when they were a mere two billion years old. Baby threads in a baby blanket of universe.

I wonder, a little, what kind of instrument, what kind of light would let me see just 36 years ago? Before I was born and before my grandma died. When there was a warm house that had always been home, a baby on the way and a blanket nearly ready for her.