I am writing this at the kitchen table while my twelve year old eats breakfast. She’s excited about going to school. She’s presenting a silent, prop-less skit she made with a friend. It’s a murder mystery. My daughter is the victim and her friend is the victim’s hair stylist. I doubt any of her drama friends read this newsletter, so I’ll spoil the ending - the hair stylist did it.

She’s been reading a lot of Agatha Christie. I remember finding Christie at her age. My daughter is a more sophisticated reader than I was; she can spot and discuss Christie’s anti-semitism, classism and racism. I didn’t really process that at her age. But she’s intrigued by many of the same things that drew me into Christie’s work when I was a kid. The careful construction of each murder. The clear-eyed detective with a mind bent enough to follow each lie around each corner to where the truth hides. The bold stroke characters that read more like halloween costumes than anyone you’d ever meet in real life.

Murder mysteries gave me a safe way to sit with violence and vulnerability.

Murder mysteries, gave me a safe way to sit with violence and vulnerability. Christie’s words came into my life at the same time as the news of the Columbine massacre. In jr high, school transitioned from a place where I looked forward to snacktime to a place where I tried to avoid sexual harassment. I read about Linnet Doyle’s murder under my desk during class. Christie’s victims weren’t safe, and neither was I. But Christie made an unsafe world feel like a murder mystery party.

Sure, every book started with a dead body but by the end everything was legible. Means and motivation neatly laid out. I understood what happened. I could never understand the real violence in my real adolescent life - the school shootings, the 6 o’clock news, the boy in math who leaned over and said he dreamed he raped me but it was only a dream, calm down.

I tried moving from murder mystery into true crime when I went to college. It seemed like it was time to, I don’t know, try to understand. I read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Published in 1966, it’s often cited as the beginning of true crime as a genre. It’s a book about the murder of four members of the Clutter family - Herbert, Bonnie, Nancy and Kenyon. Nancy was 16 and Kenyon was 15. The family was killed by two men who’d heard Herbert kept lots of cash in a safe. They wanted to steal the money and go live in Mexico. Herbert didn’t have a safe with a lot of cash. The men killed the family for $50 and a radio.

The murders didn't make the killers rich, but In Cold Blood made Capote wealthy. It was deliciously shocking for many readers. The murders took place in a small farming town in Kansas. It was the kind of place 50s and 60s white America thought violence couldn’t find. Of course, Black families could attest that violence didn’t just find rural America, it was often grown there too. The accuracy of Capote’s reporting has been challenged since the book was published. He invented scenes to make messy, pointless murders a clean, pointed narrative. I didn’t know that when I read the book. I just knew I could never consume true crime again.

Christie’s victims didn’t really exist, it was all right that they were plot devices. The Clutters did exist, they were not plot devices. They were people. Herbert and Bonnie’s older daughters had to come home and bury the bodies of the rest of their family. How could Capote dig them up for a story? He extracted so much, but what did he give in return? Everyone already knew all the facts before Capote published In Cold Blood. The murderers had been sentenced and executed before the book was even published. Capote’s only contribution was to take Clutter blood from the floors of their house and move it onto the bookshelves of readers' houses.

It was only a murder, calm down.

When I read the book, I was two years older than Nancy was when men shot her to death in her bed. In his confession, one of the murderers said he’d restrained the other from raping Nancy before they killed her. Yes, they killed her but they didn’t rape her it was only a murder, calm down.

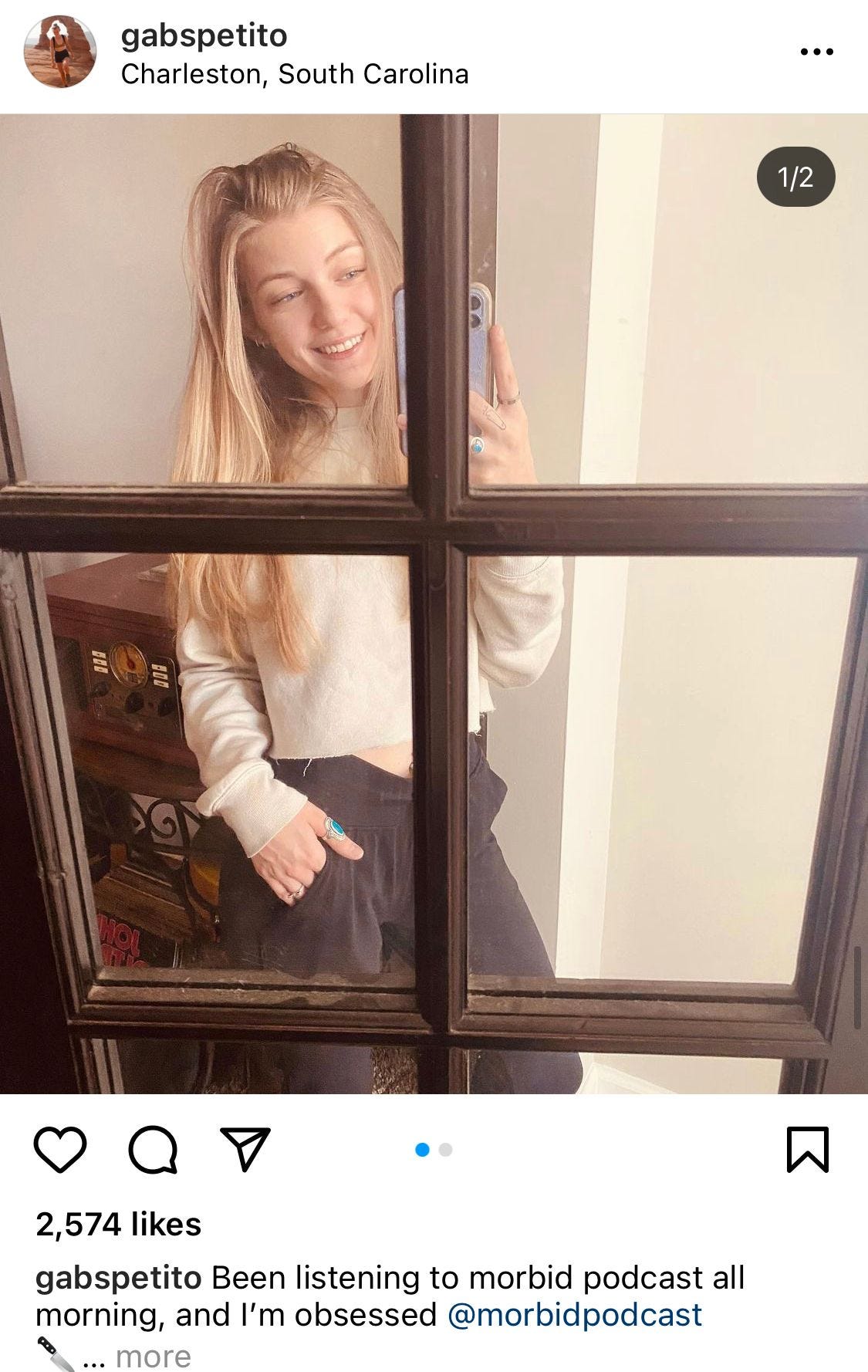

Gabby Petito, 22, was reported missing on September 11. She hadn’t been heard from since August 24. She and her boyfriend, Brian Laundrie, had been on a months long National Park road trip in a camper van. They shared their outdoor adventures on separate Instagram accounts. Initial news reports about Gabby’s disappearance ran under headlines like #VanLife Influencer Disappears.

Before Gabby disappeared, someone saw Brian abusing her on a street in Moab, Utah. On August 12, police were called because “a male had been observed to have assaulted the female” outside of a white van. The caller said they saw Brian slap and hit Gabby. After abusing Gabby, Brian got into the van and locked her out. She climbed in through the van’s window before it sped away. When police pulled the van over, Brian was driving and Gabby was sobbing. They were separated for a roadside interview. The bodycam footage is excruciating.

Laundrie is calm and accepts the role of heroic victim. He says Gabby attacked him. The police count the scratches Gabby left on his face and arms. They are seemingly unaware that fingernails are often all abuse victims have to defend themselves. Their obtuseness is confusing. Domestic violence is up to four times higher in the law enforcement community than it is in the general population. At that rate, even a non-abusive officer has some passing knowledge of why many women scratch men. As the police counted Brian’s scratches, he said that he’s got no complaints. His next words are chilling, “I hope she doesn’t have too many complaints about me.” It’s a fishing question, he wanted to know what she’d said to the officers. He didn’t need to worry. She only blamed herself.

As she cried to the police officer, she blamed her “meanness” on mental illness. She wasn't mean to Brian, she clarified. But she’s sorry for her meanness anyways. The way she is explains the way he treats her. It was all her fault. She told the officer she climbed into the van because she thought he was going to leave her in Moab. The police listed Laundrie as the victim and put him up in a motel for the night. Laundrie didn’t leave Petito alive in Moab, like she feared. Instead, he left her dead in Wyoming. Gabby’s parents reported her missing after Laundrie returned home with her van and without her. He disappeared a few days later.

Gabby Petito was a fan of true crime. She posted about her favorite true crime podcast Morbid on her Instagram. In the days after her disappearance, Morbid asked fans for help finding Gabby, a long time listener and first time true crime subject. There are a lot of true crime fans out there. Many of them use TikTok, Instagram and Twitter. The first wave of national attention happened because a large TikTok account shared details of the case. Other accounts and true crime podcasts took it from there. Some of the community formed around Gabby’s disappearance felt earnestly constructive. A lot of it looked more like the communities of conspiracy that sprouted up around Q drops during the Trump administration. In a country starved for community, for communion, I guess this is how we’re finding it.

One true crime podcaster interviewed by The New York Times said , “I think people are so into it because it is happening in real time and because you can follow many of the clues yourself that Gabby and Brian left on social media.” It’s a distasteful way to talk about the murder of a person who loved and was beloved. But it’s because of someone following those clues that Gabby was found. A YouTube Van family realized were in the Bridger Teton National Park in Wyoming at the same time as Gabby and Brian. They searched their footage for Gabby’s van and saw it parked on the side of a road in the park.They sent it into the FBI. Gabby’s body was found close by the next day. Murdered VanLife Influencer Found by Youtube Vanlife Family.

Gabby listened to her favorite true crime podcast in the days before she became the subject of a social media true crime followalong. She was in an abusive relationship. I am trying to open myself up to what true crime did for her. Maybe listening to true crime stories helped her understand something. Sometimes when someone is killed, a stranger comes along and digs them up so a story can be told. Maybe letting other people’s blood pool in our airpods is a way to witness as well as exploit.

Women disappear every day. Sometimes their bodies are found and sometimes they are not. Why did Gabby’s disappearance become a national phenomenon?

Like the Clutter case, it happened in a place and to a person that felt shocking to some. During the pandemic, America’s National Parks have become a refuge for people who can afford to travel to them while working remotely. The camper van Gabby and Brian drove across the country is part of a much larger trend. The New Yorker published an article about #vanlife as lifestyle brand in 2017, “There is an undeniable aesthetic and demographic conformity in the vanlife world. Nearly all of the most popular accounts belong to young, attractive, white, heterosexual couples. ‘There’s the pretty van girl and the woodsy van guy…’”

Gabby was a pretty white van girl and Brian was a woodsy white van guy. People posting #vanlife content are mostly white. So are the people visiting National Parks.

In 2018, Black people accounted for just 2% of National Parks visitors, while“Hispanics and Asian Americans each comprised less than 5%” This is the result of intentional exclusion. Before exclusion, there was genocidal expulsion. The land that now makes up our National Parks used to be under the stewardship of Indigenous People. They were violently forced from their ancestral lands. After the National Parks were established, the parks were officially segregated until 1945. De facto segregation lasted much longer.

It wasn’t just difficult to be a Black person in the National Parks, it was dangerous to be a Black person driving to the National Parks. In The New York Times, Tariro Mzezewa wrote about the danger road trips held for Black Americans in a country littered with sundown towns and patrol cars, “For many black travelers... the road trip has long conjured fear, not freedom. Victor Hugo Green published the first version of his now-famous ‘Green Book’ in 1936; it listed towns, motels, restaurants and homes where black drivers were welcome and would be safe.” This past is also our present. Every Black man shot by police while he reaches for his license after being pulled over is proof that driving in America is still not safe for Black people.

Many of the vans are intentionally minimal in the kind of way that provides comfort and costs money.

For those who feel safe, the road trip as lifestyle trend accelerated during the pandemic. Millennials with flexible remote work and no clear path to homeownership, have gotten into the van life. It’s a home they can own wherever their wireless roams. On Instagram there are 11.1 million posts tagged with #vanlife. Mostly, they still look the way The New Yorker described them years ago. Many of the vans are intentionally minimal in the kind of way that provides comfort and costs money. Not all vanlife is so cozy. As Jay Caspian Kang points out, “There is, of course, another type of #vanlife. If you drive to nearly any underpass in Oakland, for example, you’ll see rows of old R.V.s where unhoused families live.”

Maybe Gabby’s story resonated because she was a pretty white girl in an intentionally minimal van driving through National Parks. Some of the responses came from less community minded spaces. Some people seemed to delight in this extreme example of an influencer’s life being less light-filled than it appeared in posts. Perhaps after “hot vax summer” turned into “harbinger of worse to come summer” her gruesome end felt like a fitting close to the season. Or a fitting beginning to a worse one. For many, Gabby’s story feels timely. It should feel timeless. It’s the same old story, we’re just pretty good at feigning shock every time we hear it.

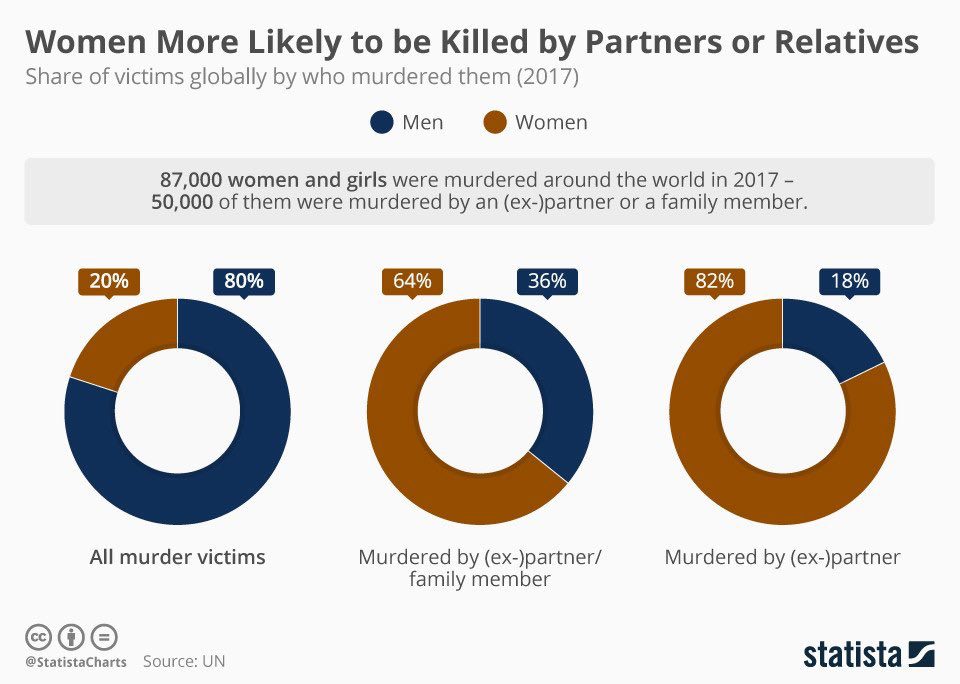

Gabby was killed by the man she slept next to every night. Many female murder victims are. He hit her before he killed her. He hit her in public so he probably hit her in private. A community member did the right thing and called police. The police didn't just do nothing, they cast Gabby as the abuser. Domestic violence doesn’t need a home. It comes for women wherever they sleep - in a house, a tent in a homeless encampment or a van decorated with the kind of stickers my kid puts on her water bottle. Water bottles. The police officers who pulled Brian and Gabby over on August 12 offered Brian a bottle of water. He refused because as an eco-conscious van lifer he prefers to avoid plastic. Man claiming to save the world kills woman instead is also a very old story.

Many people go missing in Wyoming. According to a study by the University of Wyoming, 710 Indigenous people went missing between 2011 and 2020, 85% of them were children. A majority of them were girls. Many were found, but some were not. It’s difficult to know how many Indigenous People go missing each year because of political and cultural apathy. Organizations like Sovereign Bodies are working to create databases of “missing and murdered indigenous women, girls, and two spirit people.”

They are not being helped by the media. 30% of Indigenous homicide victims are covered by the media, compared to 51% of white homicide victims. A mere 18% of Indiginous female murder victims receive media coverage. These lost are joined by an estimated 64,000 Black women and girls missing in America. Last year, the Human Rights Campaign reported that “fatal violence against the transgender and gender non-conforming people” continues to climb.

Why aren’t we hearing about all of the lost? Some of it has to do with “missing white woman syndrome”, a term coined by Gwen Ifill to describe the media’s disproportionate coverage of missing white women. Of course, white women sometimes go missing without media coverage, especially when they aren’t pretty instagrammers. But they are much more likely to be the focus of a news story. Another issue is the click economy. The news cycle driven is by clicks, once a story proves it commands attention, outlets compete for page views. Who is providing all those clicks? Well, you and me.

We have a problem but the solution is not to ignore cases like Gabby’s. Of course, that baby girl needed to be found. The solution is to provide better coverage - in every sense of the word - for every person who goes missing. It sounds like a lot. But after witnessing the frenzy around Gabby, it’s impossible to say we are not up to the task. With a 24 hour news cycle and our phones always in our hands, we’ve got the time and the means. But we don’t seem to have the will. Why?

It’s just not as fun to do the real work that protects women. It requires the slow and steady work of racial justice, economic justice and community outreach. Maybe if girls weren't raised in a culture that accepts violence against the vulnerable, fewer women would think they had to accept violence from their partners. A community member tried to help Gabby and called the police. But the police were not equipped to help her. We need to interrogate the systems that leave people in harm's way. None of this is rewarded with clicks or follows. It doesn't require national treasure hunt maps with x marks the murder spotgraphics. Almost all the work must be local because women are killed by the people they know. They need the other people they know to protect them. We need to look up from our screens and across the street.

We can build community around protecting the people in our community. Or, we can just continue in the grand tradition of Capote. We can see what kind of capital we can build with the blood of the murdered and missing. Instagrammers are already registering domains and populating color coded grids with Where’s Gabby branding. Their online community grows with each post. As I edited this piece, another Facebook detective was sharing a shocking video. This time, instead of a white van on a road, it’s perhaps, who knows, but maybe, Brian Laundrie wandering in front of a trail cam while hiding from police. By this morning there were 17k comments and over 20k shares on his post. (Update: It was not Laundrie.)

While we thread theories, bones of mothers, sisters and daughters wait to be found. If we stop scrolling, how many of our mothers, sisters and daughters can we keep from being lost? Will we work to find them? Will we work to keep them?

It’s later now. My twelve year old is sitting on the couch next to me. She’s reading, but its not a murder mystery. It’s a book about about a young inventor on a sea adventure. I am glad. There's been too much murder.

A funny thing about having a daughter? I can feel all the shapes of her face against my hand as she grows. I remember how her forehead felt when I held my hand against it during her first fever. The way her cheek pressed into my palm when she was three. She’d have me lay next her and she’d use my open hand like a pillow. Brushing tears away with my thumbs at every age. Her temples as I pull her up and back into a ponytail before school now. I hope to know all the future shapes of her face against my hand until my hands are still.

Gabby’s mother can feel her daughter even though she’ll never get to touch her again. Her daughter has been found. A cold comfort where there was once warmth. It’s more than many mothers have. So many mothers can feel their missing daughters’ faces against their hands but will never know where to reach.

The RILYA Alert Created by Peas in Their Pod, RILYA Alert informs the public about missing children of color. The alert is named after “Rilya Wilson, whose name stands for Remember I Love You Always…[she] was a 4-year-old child in Florida’s DCFS custody when she disappeared. She was missing for almost two years before anyone in that organization noticed. This alert system is named in her honor, as it is our fundamental belief that everyone should be made aware when a child is missing, regardless of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or age. Moreover, every child should be considered a national priority once reported or labeled as a missing person.”