In this newsletter, I introduce you to slightly sinister 1930s proto-online community founders, Google's surrealist surveillance ancestor, and launch a new project that just might be ... everything I've been working toward for years? It's a lot! But conveyed in digestible, chatty prose. I promise!

Okay! Let's go!

When I don’t know what to do, I garden. I’ve been gardening a lot. My yard is bursting with cone flowers, yarrow, chokecherry, milkweed, tomatillos, lumbre, chives, strawberries, marigolds, mint, lavender and a dozen or so other species. There is always dirt under my nails and on the bottom of my shows. I am the soiled goddess of a pollinator paradise because I haven’t known what to do with Pocket Observatory.

It's infuriating. Because I know WHAT Pocket Observatory is.

Pocket Observatory is a lens. It's supposed to collect light. It's supposed to helps us see through the obscurity imposed by algorithms, misinformation and AI drivel. A lot of that light has to come from your observance. But I’ve had a hard time understanding how to ethically collect and process it.

A “community” where we shared observations seemed like the best approach. But I could not find a platform or community-building hack that didn’t threaten to over-expose you. So I abandoned that pretty quickly. And then...started gardening again.

See, Pocket Observatory must exist outside of tech-defined Creator economy. But even as I rejected platforms and models, I've been trying to use common Creator solutions to develop Pocket Observatory. And like! That’s the wrong developer! I know that. I’ve known that! I’ve just had no idea what to do about it.

Until now.

Have you heard of The Mass Observation Project? Yeah, me neither until about two months ago. I was listening to a podcast while digging out a particularly pernicious weed. In a quick aside, one of the hosts briefly described a social research project called Mass Observation. It was just a sentence or two. I'll paraphrase them for you,

Mass Observation is a social research project. Everyday Britains send in observations about their everyday lives. It's a great resource for getting behind the headlines and into how people really feel about culturally significant moments.

The episode then moved on, but I did not. I stayed still, crouched between my coneflowers and yarrow. One hand on the trowel, the other in the dirt. I was stunned.

I'd been trying (and failing) to develop the negative of The Mass Observation Project since I started Pocket Observatory. But until that moment in the dirt, I didn't even know Mass Observation existed! If I could learn more about Mass Observation, maybe I could learn what to do with Pocket Observatory.

I only moved when I felt something crawl across my hand. A ladybug. I placed her on a columbine. Go forth! Feast on aphids! Finished digging out the damn weed. And then read, walked, wrote and read some more.

I honestly just wanted to figure out how to keep my job. (Pocket Observatory is my job!) I certainly didn't expect to find proto-online community founders, Google's spiritual surveillance ancestor or archival material that made me weep? But life is just really wild like that sometimes.

Okay. This is the part where I tell you about The Mass Observation Project's surreal (literally) and sinister (slightly) predecessor, Mass-Observation.

If you really want a fun deep-dive into Mass-Observation, please read Caleb Crain's excellent New Yorker article Surveillance Society. It's one of the most accessible resources I've found on the subject. I'll be sharing excerpts here. But truly, the whole thing is worth a read.

Mass-Observation was started by three British men - a poet, a wannabe ethnographer, a filmmaker - in 1937. Here's an excerpt from Crain's article,

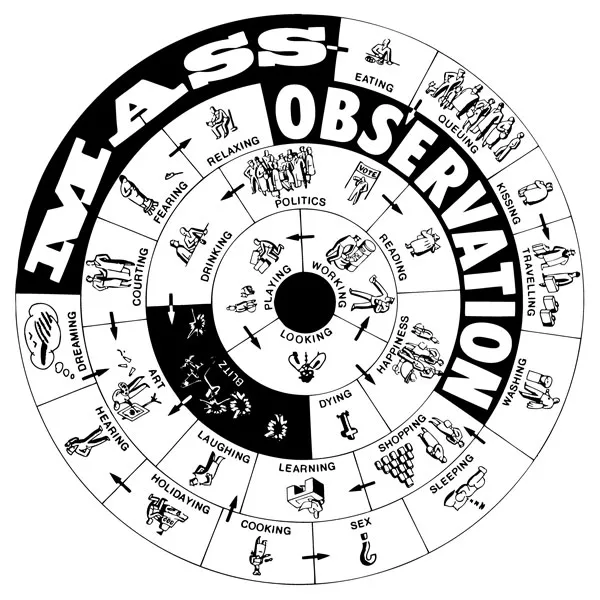

On January 30, 1937, a letter to the New Statesman and Nation announced that Darwin, Marx, and Freud had a successor—or, more accurately, successors. “Mass-Observation develops out of anthropology, psychology, and the sciences which study man,” the letter read, “but it plans to work with a mass of observers.” The movement already had fifty volunteers, and it aspired to have five thousand, ready to study such aspects of contemporary life as:

Behaviour of people at war memorials. Shouts and gestures of motorists. The aspidistra cult. Anthropology of football pools. Bathroom behaviour. Beards, armpits, eyebrows. Anti-semitism. Distribution, diffusion and significance of the dirty joke. Funerals and undertakers. Female taboos about eating. The private lives of midwives.

The data collected would enable the organizers to plot “weather-maps of public feeling.” As a matter of principle, Mass-Observers did not distinguish themselves from the people they studied. They intended merely to expose facts “in simple terms to all observers, so that their environment may be understood, and thus constantly transformed.”

In another, more succinct description, the founders said they were setting out “to create an anthropology of ourselves.” At different times, Mass-Observation was declared a science, an art, a project, a movement.

From 1937 to the mid-1940s, the Mass-Observation sent out prompts to people who'd signed up to be Observers. The prompts were called directives. The directives were wide-ranging - touching upon interiors, sexuality, politics, technology, daily interactions. They were quirkily curious.

One asked Observers to list the items on their mantel. You can learn a lot about a culture by the objects its people place above the hearth. There were directives about smoking habits, meal times, and the Munich Olympics.

Hundreds of observers anonymously responded with essays, lists, images, sketches. The observations came together to form a body that subverted the mono-narratives pushed by the British government and other ruling interests.

Penguin published a book of them in 1939! Other books followed! Mass-Observation represented the lives of everyday British people. It deemed them worthy of study. And that had never really happened before.

Okay, you know the "They had us in the first half, I'm not gonna lie" meme?

Learning about Mass-Observation was kind of like that meme. During the first half of my research, I was totally enthralled. And then I got to the second half. Yikes.

Crain writes that Mass-Observation's founders were trapped in the very British liminal space Orwell called, "lower-upper-middle-class." They were raised to be gentleman, but there wasn't enough family money to support their raised expectations.

There is a sense that resentment might have motivated Mass-Observation. As much, or perhaps much more, than representation. Many mass observations came from working-class people. This gave workers a voice! Which was great. But in the decades since the project, there's been “suspicion in the minds of some critics. Did the leaders of Mass-Observation take an interest in workers merely to express dissatisfaction with their own socioeconomic niche?”

I mean...it seems like...kinda?

As I understood more, Mass-Observation became less and less Observer-centered. The Mass-Observation lens turned observers into specimens. This taken along with the class dynamic just kind of...gave me the ol' colonial imperialist power ick? (I am sure that is exactly the phrasing an ethnographer would use.)

The founders wanted to use everyday people's observations to subvert prevailing narratives. And like, Okay! Love that for us! But also...to what end?

Well...mostly the founder's ends.

They were all Surrealist-adjacent artists striving for recognition. They understood that great art often emerges from that murky space between lived experience and official account. Through Mass-Observation they were able to extract at scale from that space. They collected observations and then mined them for their own films, politics, poetry, prose, prestige.

They believed Mass-Observation bound art, literature and science together. And honestly, after reading some of their self-serious writing it really does seem possible they thought they were founding the movement that would supersede Surrealism. Maybe it would have, if they could have come to some consensus about the nature of the thing they were building.

Crain writes that the founders were, “were a fractious triumvirate from the outset, never even agreeing whether their group’s name meant observation of the masses or by them” And like! Whether Mass-Observation was a way to give a voice to the everyday person or the father of surveillance capitalism really depends on that distinction!

The distinction was made during WWII. One founder wanted to use Mass-Observation’s data collecting capacity to get government contracts. Mass-Observation could design directives that helped the government track general moral. Another founder called this “home-front espionage.” He was right. No matter. By May 1940, Mass-Observation began secretly sending “weekly reports on morale to the government.”

And yeah, Google used their own data-collection/surveillance capacity to get contracts with the US Department of Defense too! Because no story is new in the history of the world, ever. Amen.

By the end of the 1940s, none of the founders remained. The project was turned into a private market research company. It eventually merged with an advertising agency. This is darkly funny. But it's not surprising.

The details of our daily lives, and our perception of those details, are a very valuable dataset. And Mass-Observation never operated from a pro-Observer/anti-extraction framework. So like! Of course the whole thing devolved into the 1950s version of Google giving up all its pretend ideals to embrace surveillance capitalism and targeted-ads.

For all its faults, Mass-Observation collected an incredibly rich archive of everyday observations. Those observations continue to subvert official narratives. The influence of MO’s original founders can never be completely scraped from the project. But it is far less present than it used to be.

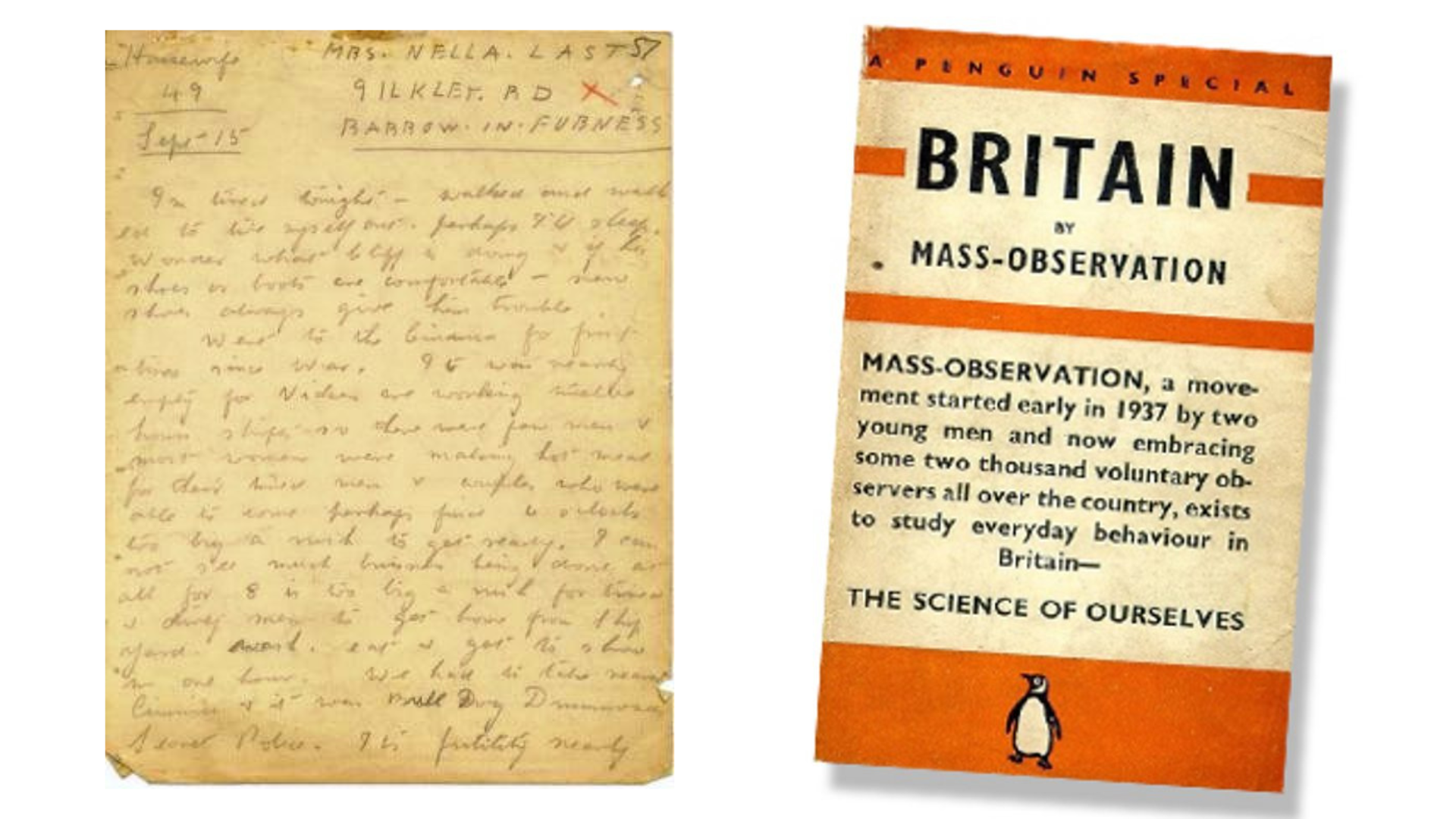

The archive belongs to everyone now. Researchers can access the archive with a simple online appointment at the University of Sussex. (And if you have a favorite author writing about Britain around WW2? Odds are they have!)

The Mass Observation Project

In 1981, Mass-Observation was born-again through the The Mass Observation Project. Run out of the University of Sussex, The Mass Observation Project has the institutional guardrails the original M-O lacked. Because it is more transparent, it is more people focused.

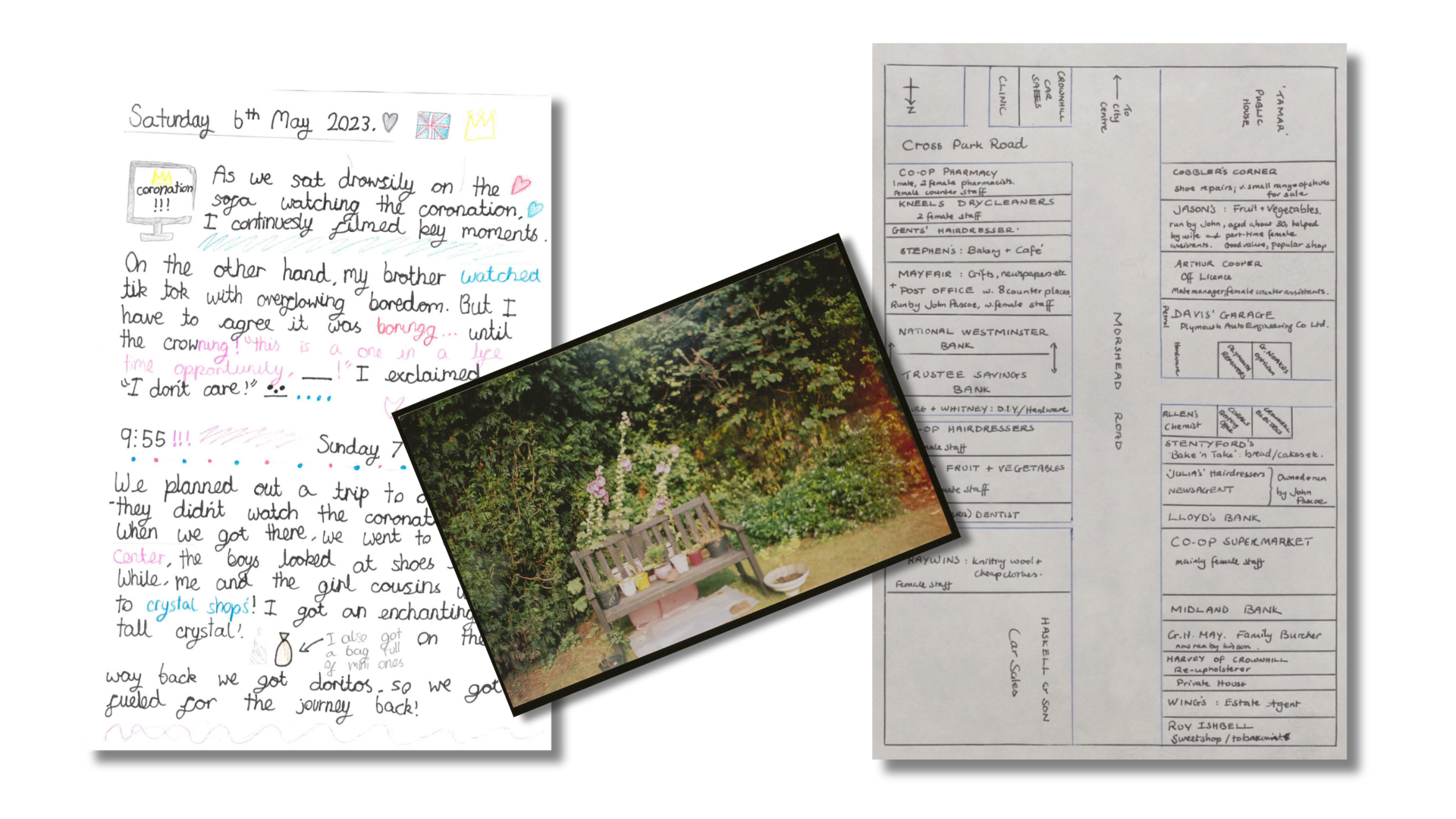

Seasonal directives are sent out to anonymous volunteer observers. They have a lot of the quirkiness of the Mass-Observation directives! Which is great. They also lack the creepiness of the some of the original directives. Which is also great.

I’ve read through every digitized directive I can find online. The earliest ones are more like chatty letters sent from the project directors to the observers. Full of questions and peppered with asides. By the 2000s, the directives seemed to adhere to a template. Multiple questions, each given its own section. Little call out boxes with instructions. The Mass Observation logo neatly embedded in the top of the page.

A broad curiousity unites the decades of directives. And a distinct openness seems to course through all the observations. According to the The Mass Observation Project, 500 people are “actively writing” observations for the project. Some of them have been writing for “many years, meaning you can trace many writer’s changing thoughts, situations and opinions over years, if not decades.”

In total, they've had over 4,500 observers since 1981. Their observations form a body that works to subvert and complicate the narratives pushed by those in power. And because they have been properly archived, that work will continue long after each volunteer has ceased to observe in this time and space. The archive is open. You just need to make an appointment.

I've spent some time wandering through digitized responses from both iterations of Mass Observation. Some are typed, some are swirls of handwriting I can't quite decode. Sometimes the observations come from children - the crayon is faded, but still seems bright enough. There are sketches, maps, photographs, diagrams, and timesheets.

I found myself wanting to frame each one. But they don't belong to me. I am just grateful for the chance to observe them.

Okay. So we all have a general understanding of Mass-Observation and The Mass Observation Project. How does this help develop Pocket Observatory?

GREAT QUESTION! Let me explain!

Mass-Observation helps us observe some of the pitfalls of the community founder model.

It's been difficult for critics to categorize Mass-Observation. Is it science? Art? Project? Movement? But I think one thing is fairly obvious. Mass-Observation was a proto-online community. The three founders were community founders. And the observers were their followers. (This does not take away from their observations!)

Our current form of capitalism insists that creative work is content and that content should be free. Content is how you get people into your community. And communities should cost people money! People who produce creative work must become community founders if they want to make a living.

This makes a lot of them uncomfortable. And so a lot of community founders claim their communities are not really centered around them as people or public personalities. Instead, they are just facilitating a community centered around connection, representation, amplification. I think a lot of them really mean it! i know I did when I said it in the past!

But the community founder has the same problem Mass-Observation faced. Fostering online engagement is like a directive. There is a prompt and a response. The most engaged communities are the most successful communities. High engagement requires the development of online relationships through sharing experiences, advice, questions - the information of their lives! All those responses become an an archive of very valuable data, protected by very few real guardrails.

Very few community founders are building communities on platforms with real privacy protection. Every time a community member writes a comment, shares an observation, clicks a link - their data is being collected by a tech corporation. This is incredibly difficult to get around! I shut down the community I tried to stared after leaving Substack because I could not figure out how to make it private enough.

But let's say a community founder built or found a very, very private platform! The community founder is still prompting and collecting community data FOR THEIR OWN ENDS. Even if that end is just converting non-paying consumers to paying subscribers. And I mean I GET IT! (And I've done it!) Why?

Because none of these business models work for the people doing the work.

If everyone who reads my writing each week paid me JUST A DOLLAR A MONTH, I'd become the main breadwinner in my house. Can you believe that? Me! Who never thought she'd be anything but a housewife!

Instead, people consume my work without paying for it. And I am so stressed about money, I've applied to Costco and Barnes+Noble for the third time this year. (They never call me for an interview. But I keep trying.) So I really, really, really get the people who decide to "found" communities. It is impossible out here.

But getting it doesn't solve the archived problem. How can a single person be trusted with that? How can they protect it? How can they protect the people contributing to it? How can they keep themselves, or others, from mining it?

Like in 1937, when M-O's founders were writing flighting words about a new science, I don't think any of the thought they'd be fighting over whether to use Mass-Observation to help the government manipulate the masses! But then...in 1940...that's where they were!

Do you see? This business model doesn't work for the people consuming the work either! It exploits, leverages, exposes them! You deserve better than that.

Understanding Mass-Observation helped me understand, that no matter what happens here, I cannot become a community founder. Ever. If the only way I can get people to pay me for my work is to become a community founder? It's just time to stop writing. (Barnes and Noble! CALL ME!)

The Creator Economy is the Asylum We're Being Raised In

Engaged communities like the Swifties are data-rich ecosystems exploited by surveillance capitalists.

The Mass Observation Project helped me appreciate the radical power of the prompt in everyday life.

Prompts are an incredible tool for interrogating things one might not have ever properly observed otherwise. I really appreciate the work, the thought, the curiousity that seems to go into each MO Project directive. I spent some time responding to old ones on my own this month. I could not believe how much I observed because of them!

Of course! Prompt power is not benign! The questions we ask ultimately determine the answers we find. Generally, modern MO directives seem to come from a place of open curiosity, with lots of room left for different experiences. But it's something to be aware of whether you're being prompted or doing the prompting.

The Mass Observation Project also reinforced the individual and institutional value of open-source observation.

Sometimes I dream of creating a properly protected, and also radically open archive of all your observations. But learning about The Mass Observation Project helped emphasize what I already knew! Which is ummmm….I am not an institution! The Mass Observation Project has an entire budget! Staff! Interns! It’s supported by an entire university! It's okay I am not an institution because...

Collecting and archiving observations, even transparently, is not just beyond the scope of Pocket Observatory. It's antithetical to its mission.

I meant it when I said Pocket Observatory is the (accidental) negative of Mass Observation.

The Mass Observation Project was created for the researcher. Many observations form a matrix of shared reality. Pocket Observatory was created for the observer. A single observation expands into a wave of potentiality.

Is that clear enough? (I am laughing as I type that because….it is, if you’ve been here long enough. But if you’re just dropping in…well…I’m sorry.)

Okay! So! If Pocket Observatory can’t develop without your observations, but I also can’t collect observations? Where does that leave us? It's so simple! I just need to do the inverse of what what The Mass Observation Project has done.

I need to create (drum roll please)....

The Pocket Observation Project

Pocket Observatory holds The Pocket Observation Project. I will continue to write essays and little letters from my Pocket Observatory. These will continue to be available to everyone. I think they will just get better and better, honestly. The Pocket Observation Project gives my work context. I am so excited about all of it.

Monthly Observance

Each month I will send out the Pocket Observation version of a directive. Only directive is definitely not the right word. This isn't for researchers. It's for you, the observer. So we'll go with something less authoritative. How does Observance sound?

I like it too.

Like Mass Observation's directives, Observances will be specific, quirky, curioous. They'll cover current events, interior lives, exterior walls, design, science, politics, technology, etc. There will also be prompts related to things Western cultures stopped traditionally observing during the "Great Enlightenment." Let's get metaphysical.

Each observance will be carefully considered and constructed. A little set of prompts meant to help you sit down and think beyond algorithms, headlines, and the mono-narratives of the powerful. (It's a practice worth developing as we prepare to dive into designed chaos of the US presidential election. Ahem.)

Occasionally, I'll invite guests from other disciplines to write the monthly Observance. The prompts a neuroscientist comes up with will be very different than the ones I create!

Recording and Sharing Observations

I'll be sharing all of my own responses to the monthly Observance. My observations will be recorded in various ways - essays, audio, sketches, lists, photographs. I'll post them for you to peruse in The Observatoreum.

I anticipate you will observe in different ways, at different times. Often, ruminating on the month's observance will be enough! Sometimes, you will want to record your observations through writing, images, audio. When you do record your observations, I hope you collect them for yourself, for your family, for the people who come next. You're helping to create and preserve a distributed Pocket Observation archive. I think that's really neat.

One possibility? We could treat Observances as paid features. I could open up for submissions, pay you for your Observance and publish it with your byline or anonymously. That feels more ethical than other options. I am still thinking on it.

In the future....

I’d like to send you the monthly Observance in the mail. It’d be nice to sometimes help provide materials you need to capture your observations. Papers, pens, fieldnote journals.

I am also imagining meetups where we go observe something together. A play or an exhibit or a moment. I hope to make some elements of The Pocket Observation Project tangible this fall.

But for now, I am just very, very excited about getting going with what we've got.

The official Pocket Observation Project launches August 1st

When it launches, there will be a document that explains the ins and outs of becoming part of the project.

For now...

We're doing a little soft launch. Figuring out the bugs. Getting some feedback. If you are a member of Pocket Observatory, you'll get a pilot Observance delivered to your inbox this weekend.

If this piece gave you something to think about for a day, a week, or a month consider making a one-time donation so I can keep writing! Buy me a pen, or a used book, or 48 minutes of childcare!