My first baby was just a year old in 2010 when a dude who liked to drink Bourbonreleased an app called Instagram . It was only available on iPhones. I didn’t have an iPhone so I couldn’t use Instagram. But the moms who had it, told me about it. They said it was like Hipstamatic, a photo filtering app, with one important difference - Instagram was social. It was a digital space where some of the moms in my neighborhood started following moms from other neighborhoods, states, and countries. They posted pictures of themselves being moms, but filtered. At playdates at parks that first year or two, half the moms had the hardware you needed to run the Instagram app. The other half looked over their shoulders.

The first people on Instagram helped to define the space. New features were built around those people’s use and preferences. I was not one of those people. I didn’t get an iPhone until March of 2012. My first post was a lo-fi filtered picture of my second child when she was seven months old. There are three comments on the post, one of them was from a nice mom in my neighborhood who was already using the app to create content. She wrote, “Welcome.”

I was happy to be there. Much of my time was spent alone with my kids. I felt both overwhelmed and underwhelmed by the work of the day. With Instagram, I made a chain of meaning out of the pictures I posted for my couple of dozen followers. A baby on her blanket on the ground. A pile of dirty dishes. This new thing called a “selfie.” It was my turn to sit at the park, checking for Instagram posts from women writing about being alone in their houses with their kids too. Their confessional rants about dirty dishes and housework felt like communion. As the platform gained popularity, that communion became community.

The women put up pictures of their dirty kitchens, their crying children. They shared stories about birth and house work. Some of these women had jobs outside of the home, but many did not. But I knew they were working, even if they weren’t paid for their work. They were doing the work I did. Instagram helped make carework visible and, for some moms, it made carework profitable.

The Instagram heart you tapped to like a photo was declared valuable by community consent. Those hearts became a fiat digital currency. The exchange rate was steep, but if you got enough “hearts,” sponsors were happy to help you exchange that digital love for cash. Moms with enough followers and engagement could post an image of a bottle of soap next to a sink full of dirty dishes and get paid by the soap company. Brands sponsored “mommy blogs” with cash and free product for years before Instagram. Any caregiver desperate to make some grocery money knew that hosting Google Ads on a blog with enough traffic could be profitable. Mommy blog clickbait often existed because those moms were trying to figure out how to pay for school clothes for their kids.

Some mommy bloggers transitioned to Instagram. But many mompires were built for the first time there. A photo, a brief caption and the round robin support of moms sharing each other’s Instagram handles made monetizing motherhood truly accessible. It was thrilling watching these women, some of whom I knew, getting paid for work we’d been raised to believe women were born to do for free. People scoffed about moms ruining Instagram, but I thought they were revolutionary. They’d formed a market for their unpaid labor in the home.

Each Instagram post of caretaking was a representative token of unpaid labor.

Or at least their representation of unpaid labor. These women weren’t being paid to be caretakers or community builders. They were being paid for their online depiction of that labor. This is an important distinction I could not discern in those early years. Each Instagram post of caretaking was a representative token of unpaid labor. The token was often filtered with Amaro. Tokens of unpaid labor were only valuable when they were created by moms who were able to build a community and remain relevant on the platform. The success of an Influencer Mom depended upon her personal brand and ability to navigate the digital space. She had to be unique while still following the rules of the filtered world.

When I started living parts of my life on platforms, I didn’t even understand what a platform was. There was no easy way for me to understand that each platform is its own world. A world with its own rules - biased algorithms, networking, and scripts for engagement. I had no idea I was being influenced. The term influencer, in its current form, didn’t exist until 2015. Some moms were being paid to represent compositions of caretaking. That was fine. But I didn’t know to ask what those representations were doing for the real work of care, paid and unpaid.

Moms behind on bills tried to commodify their carework. I was one of them. There was something quietly mortifying about the time I tried to photograph a flat lay of my children’s bottles and diapers. I couldn’t get any of it to look right. But I just knew that if I finally solved the problem of engagement, I’d make some grocery money. We were all so naive.

Instead of building something new, some mothers decided to import inequity from the physical world to the new digital one.

That naivety isn’t an excuse for many of the problems many moms created on the platform. We were given a world we could hold in our hands. Instead of building something new, some mothers decided to import inequity from the physical world to the new digital one. They mined the insecurities of their followers. They exploited underpaid caretakers while sharing pictures of linen-draped children.

Perfectly tousled women preached a secularized prosperity gospel while ignoring systemic inequality. Instagram feels like an old world now. Sometimes it’s easy to talk about Instagram as if it’s in the past. But the moms are still on Instagram. (Heaven knows, I am still there. Want to follow me?) Some moms continue to infuse value into the market while others sink.

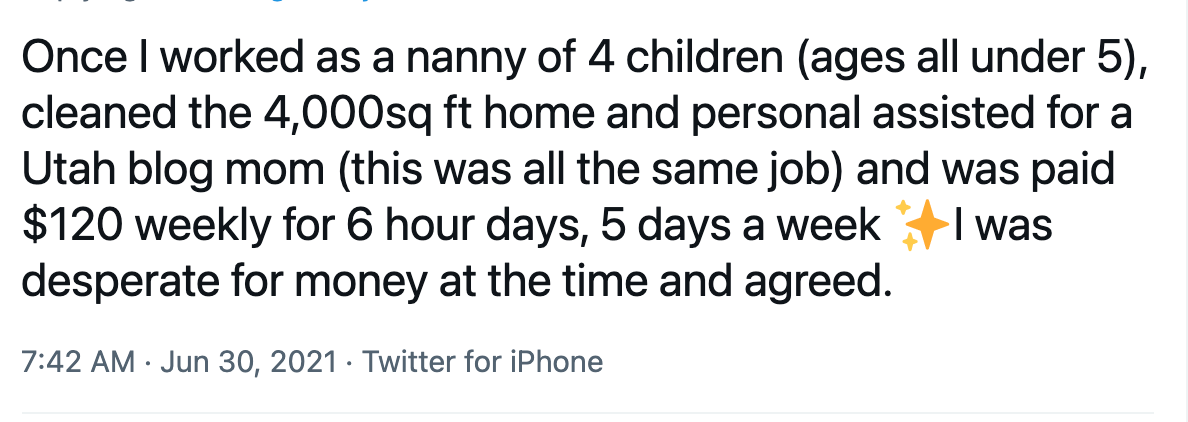

It’s not just Instagram where women’s labor has been exploited, of course. When I asked women on Twitter and IG about their lowest compensation for labor, the answers came swiftly. A Black woman was offered a Starbucks card in exchange for hours of DEI consulting at a workshop, the other consultants were paid. Woman after woman had stories of finding out their salaries were $10k, $20k, $30k lower than male counterparts in the same position, in the same company.

A lot of the stories circled around the labor of caretaking. A nanny was offered $7 an hour for full-time work in San Francisco by a wealthy family. That’s $14,650 a year in a city where HUD considers AN INDIVIDUAL earning anything below $82,200 “low income”. More than one SAHM wrote that friends and acquaintances asked them to nanny for their children full-time for free. This seemed reasonable to the people asking, since the SAHM were already “home with with their own kids and doing nothing.”

Sometimes it's the influencers doing the exploiting. One woman was paid well below minimum wage for a nanny position with a well-known influencer. She tried to get a second job to make up for the lack of compensation. The influencer told the woman she couldn't continue to nanny if she took on more work after hours.

It's no surprise that Instagram's potential to make at labor seen and seen as valuable has been so appealing to so many caretakers. Instagram still forms a chain of meaning for me. If you were to ask me why I am still on Instagram, I’d probably say, “community”. Caretaking in America is isolating and Instagram is a place where I can connect with people. But Instagram doesn’t think most people come to its platform for connection, they think they come there for entertainment. And the people in charge of Instagram think entertainment in 2021 looks like TikTok.

Changes are coming to video on Instagram 📺

— Adam Mosseri (@mosseri) June 30, 2021

At Instagram we’re always trying to build new features that help you get the most out of your experience. Right now we’re focused on four key areas: Creators, Video, Shopping and Messaging. pic.twitter.com/ezFp4hfDpf

In a video last week, the director of Instagram said that Instagram was “going to experiment with embracing video more broadly”. He insisted that IG is “no longer a photo-sharing application or an application to share square photos." The app will start embracing video by inserting longer videos in each user’s instagram feed, whether they follow the creator or not. Kind of, exactly like, TikTok. As Instagram pivots to adopt TikTok’s viral video format, it’s unlikely it will leave behind TikTok’s profound issues.

As deep fake technology is rolled out as downloadable filters, TikTok users are making themselves look like they are a different race or age. Coconutkitty143 is an account run by a grown woman, but she’s changed her face to look like a thirteen year old girl. In examining her account, Rebecca Jennings wrote, “the line between 'typical influencer FaceTune magic' and 'actively impersonating a minor' appears to be crossed.” All of Coconutkitty’s content is sexual and her website links to an OnlyFans account where she gets fully nude with her middle-grade face. “She has nearly 12,000 subscribers who pay $10.99 a month (you can do the math).”

And there is, of course, the old-fashioned problem of most people never making a nickel for their labor on behalf of the app and its audience. TikTok has been lucrative for a very small percentage of creators - many of whom take the work of others and repackage it in abled thin whiteness, the content that TikTok algorithm favors. Will Instagram be using TikTok’s AI to drive new video virality? Technically, they could. Bytedance, TikTok’s parent company, is now selling their algorithm and AI to interested companies. A development that almost makes me want to get shot back to the stone age.

But even if they have their own algorithm, Instagram has been frank about their goals. They are not seeking to provide a place of connection, they are looking to entertain with mass engagement. In copying TikTok’s method of achieving that, IG will also mimic all of it’s profound issues - while still holding on to its own.

I have a little over 13,000 people in my Instagram community. It’s a place to share my life and my writing. When I write for outside outlets, my IG community supports the publication’s dedicated SEO teams. When I write for my newsletter, every single piece gets read outside of my newsletter subscribers because of my Instagram community. I’ve not got millions of people following me, but the people who are a part of my community see me and are anxious to have others see me too. It is a valuable community in that way. But it’s much more valuable to me, in another profound way.

That number of people in my IG community, currently 13,456? It’s not one number. It’s 13,456 numbers. And each 1 in that sum represents one person. One whole valuable person. They are a world, not a number. When a whole valuable person reads something I write or taps that little heart on an IG post, I feel a deep obligation to them. Not one single person has to spend a moment of their short-time on this planet engaging with my work or my life.

I am not against monetization. And certainly what I do online takes labor. But as we move into this next phase of content creation and the creator economy, I just wonder,

How can we do this right for women? For mothers? For Black women, Indigenous women and Women of Color, if we still have not figured out how to value their labor in the real world? And how can I continue to try to build windows into a better world on a platform hard-coded with racism, ableism, and misogyny? If I choose to leave, where will I go? And how will anyone ever see me? And how will I see them? And if we need to SEE labor depicted to value it, what does that mean for every caretaker laboring the way caretakers have always labored - behind closed front doors, in sick rooms and late at night?

Of course, monetization is still kind of a big word for what most caretakers can do with IG.

A month ago, I got an email inviting me to participate in a content campaign for an ice cream company. July 8th is National Freezer Pop Day, apparently. There was a link in the email to an influencer campaign for ice cream pops. If you wanted to be chosen to do the campaign you had to complete its tasks: promoting a coupon, creating an original instagram story about the ice cream product, and an original instagram post for the product. This content had to be sent to the campaign manager for approval before posting. This may not sound like a lot of work, but it is. Especially if you’re a young mother with kids. It means staging an editorial photoshoot in your own home with an unruly crew.

A shoot about ice cream pops will get more engagement if you do you one of three things:

1. Your kids are in the IG post and story

2. You are in it, eating the pop, dressed well, with nails, hair and make up done

3. You are sitting behind a pile of laundry, wryly eating the pop instead of doing your “actual” work.

Incredible bonus points of engagement are awarded to anyone who can figure out how to compose a photo including all three elements.

Your post and story contain need to be made up of well composed images, lovely lighting and copy that is both authentic and a call to action. Without those things, sponsored posts are a liability. Unfollows over a poorly delivered sponsored post are swift, which hurts in the moment but are mostly a problem long-term. Women, especially caretakers, lose community members they’ve come to rely on for connection. And, on top of that, no company is going to trade your instagram hearts for cash if you can’t deliver enough of them. All this means that, depending on the ambition or desperation of the person, meeting this campaigns requirements could take hours, if not days.

Here’s how campaigns like this turn out for the average caretaker trying to find a way to make ends meet in an exhibitor economy.

This could be the beginning of something, maybe grocery money, maybe more. So she finds clothes that coordinate with the color of the popsicle in her kids’ drawers. She slicks back their hair into parts and ponytails. She hasn’t gotten dressed for a few days - the baby is still spitting up so much, there’s little point. But for this she slips on a dress and slicks on some lipstick. She clears a space in her kitchen and positions the empty box of ice cream pops before calling her kids into the room. And then, quickly because ice cream melts, she’ll pull the kids around the box. Her phone is propped on a stack of cookbooks. It’s just a tiny bit too low, so she slides a few weeks of bills under it to lift it a bit higher. Someday she’ll get one of those set ups the big influencers have, but for now this will do. A pop for each kid, run to the phone, turn on the self-timer on the camera. Run back and set herself up, quickly, quickly, quickly.

This could be the beginning of something, maybe grocery money, maybe more.

“Smile!” or “Just lick the popsicle.” or “Can you please look at the camera?” and then she smiles, but did it already take the photo? She gets up to check, sets the baby on the ground. Dammit, she wasn’t looking. She does this five more times until one kid has eaten their entire freezer pop, one is whining about wanting to finish their show and the three year old is crying because the pop melted onto her hand. She wipes her hand on her mom’s dress while she cries. Ice cream gone, dress smeared, the mom sighs. One of those will have to do.

It’s time to make an IG story about the pops now. The kids are bored, so she’ll just hold the empty box and talk about eating ice cream with her kids. She’s not sure how the pops taste, she didn’t get one. But she says they’re delicious.

She uses Lightroom to edit the photo after the kids are in bed. And writes the caption, three times. She’s not sure how to be engaging and authentic about ice cream pops. It’s hard. Then she edits the video down to fifteen seconds. Staring at herself talk on the screen, she thinks again she would look better if she had a light ring or maybe just more sleep. One hour before she goes to bed and one hour and fifteen minutes before her baby wakes up for his first feeding, she sends it all in into the campaign manager to get approved. When she wakes up, there’s an email. They’re approving her content.

She’ll be paid with a share in their stories. They have nearly 40,000 followers, much more than her 1,576 followers. She hopes to get some of those people to come to her account. In her head she’s hoping for ten percent of their following. She worked so hard on the campaign. This could be it. But in reality, she’ll get two or three new followers. The rest of her compensation is a coupon for the product she spent hours creating marketing material for in her kitchen. At Walmart, a box of the pops is $1.75. She used her coupon to pay for the pops in the shoot.

That night when she folds laundry, she pulls out the dress she wore for the shoot. The stain from her daughter’s sticky hand didn’t come out in the wash.

That compensation? That's what I was offered for that ice pops campaign. From a company with a multi-million dollar yearly revenue stream that depends heavily upon the labor of women like me to do their marketing. In a recent interview, Joaby Parker, the marketing manager of the company said,

“We actually use social media very heavily." According to the piece, the ice cream company's goals "are to drive product trial and retain customers. The company relies on original content the marketing team creates, as well as on hundreds of influencers who drive content through photography, video, product use and product testing, Parker explains."

I didn't do the campaign. But our woman? The one with the stained dress? She'll keep laboring every day, raising her children, volunteering in the PTA, watching kids when neighbor's childcare falls through, caring for ailing parents and sick siblings. She won't get paid for any or most of her work, but maybe she can finally figure out a way to get paid for exhibiting it. And so, with that pile a bills of a little higher every month, she'll take on the next campaign that lands in her inbox. And hope this time it's different. Maybe this time, if she makes the right kind of video, it will be.